Psilocybin Summer

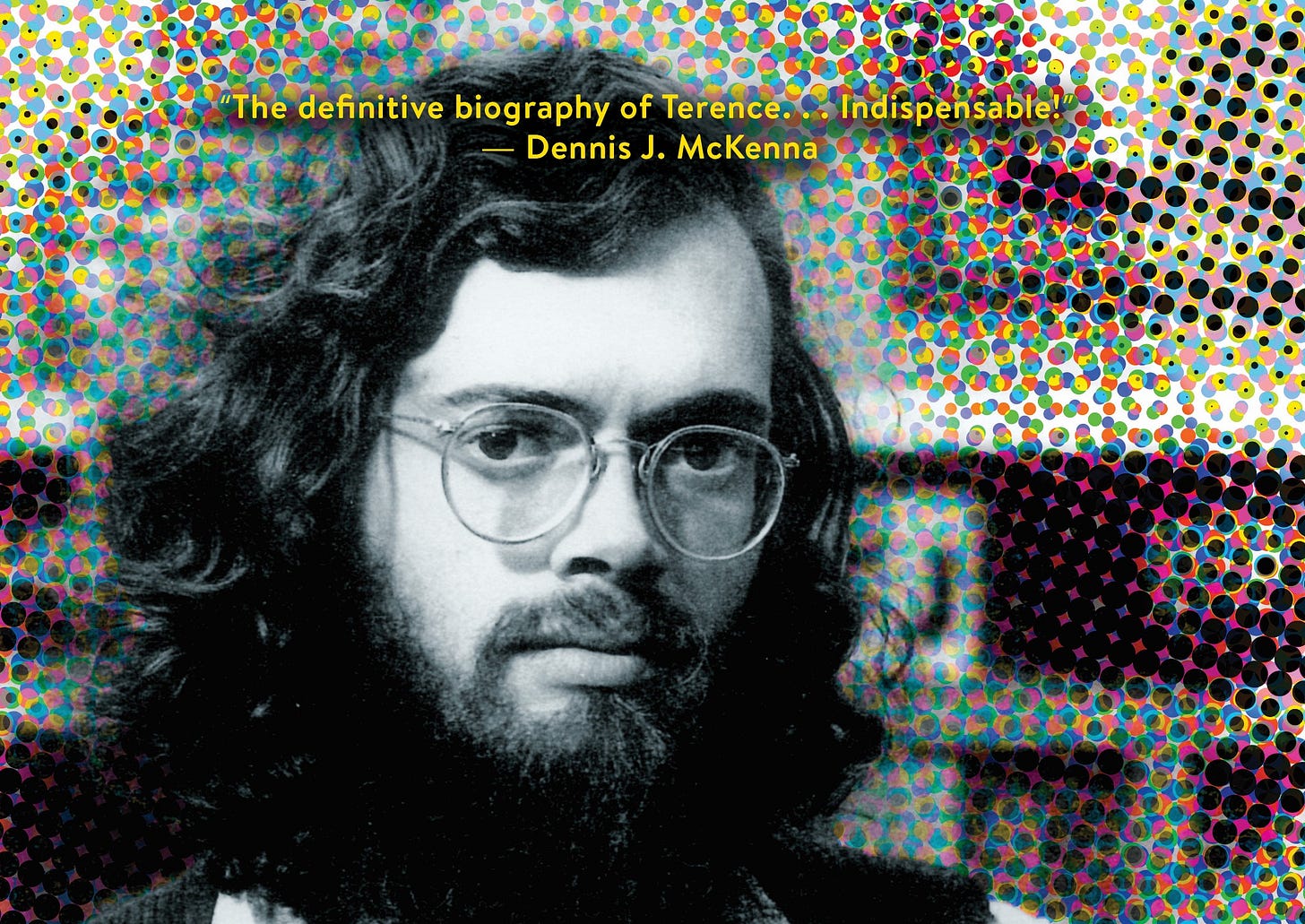

An excerpt from Strange Attractor: The Hallucinatory Life of Terence McKenna by Graham St John

This excerpt is taken from Strange Attractor: The Hallucinatory Life of Terence McKenna (MIT Press, Sept 30, 2025) by Graham St John (Foreword by Erik Davis). It takes up the story of the breakthrough in Berkeley in 1975, when the McKenna brothers discovered a method to cultivate the Psilocybe cubensis spores they had retrieved from La Chorrera, in the Amazon basin, in 1971. For Terence, who is completing his BSc degree at UC Berkeley and is in the immediate wake of a relationship fall out, the discovery marked a new era of transmissions from the mushroom muse and coincided with a new romance. The long-fantasised return to the Amazon is revealed as a driving mid-seventies motif.

Lately of broken heart, Terence threw himself into a state of hypermanic activity centered on trying out methods of cultivating P. cubensis in a greenhouse he built from disused windows in the bottom of his yard at Carleton Street, Berkeley. It is a lonely period of self-examination and mounting financial pressure, worsened by persistent migraines and a long series of failed trials. However, in the spring, working with a student colleague in the agronomy department at Colorado State, Dennis succeeds in germinating mycelial cultures on potato dextrose agar in the tissue culture lab. He then stumbles upon an article in the journal Mycologia describing a simple method for growing fruiting bodies of mushrooms in mason jars on a substrate of sterilized rye grain.1 It is a joyous occasion. Terence is informed and modifies his technique. Arriving home from a long hike in the Berkeley Hills one day, he enters the greenhouse to clean and replace the beds.

And there they were! By the dozens, by the hundreds, huge picture perfect specimens of Stropharia. The dark night of the soul had turned my attention elsewhere, and in that moment they had perfected themselves. I was neck deep in alchemical gold! The elf legions of hyperspace had ridden to my rescue again. I was saved! As I knelt to examine specimen after perfect specimen, tears of joy streamed down my face. Then I knew that the compact was still unbroken, the greatest adventure still lay ahead.2

Through ingenuity, persistence, and collaboration they had succeeded in growing the fungi’s carpophores “whose appearance,” writes Terence, “was exactly like those I had known in the Amazon.”3 With the mushroom sprouting in his Berkeley backyard, “the teacher” returns.

By late June 1975, Terence is full of optimism. He had moved to Oak Grove Avenue, North Oakland, sharing with a “countrified friend” who had gown “temporarily tired of the pastoral life.” The renters pool their money to rent a “much posher, yet still alien, house.” The place features “white walls a la 2001—the last reel.” As the dark clouds recede, his outlook improves, describing to Watson his effort to heal the “still gaping wounds” resulting from recent “betrayals.” Putting his relationship and his studies behind him, the summer instills a confidence that is hoped will help alleviate his cluster headaches and permit a devotion to the new growmance. The impression builds of a final semester dedicated not so much to course work as to the “agricultural hobby” that begins to claim his time. Over the previous three months, he had nightly labored until 2 or 3 a.m. “Many blind alleys were exhausted and gallons and gallon of rye were lost to the demon contamination,” Watson learns. “At long last however the parameters were defined and success followed hard apace.” The results were wondrous:

It is definitely the most streamlined vegetable psychedelic I have encountered. It’s chief joy, aside from the lack of residual toxicity, is the wonderful tryptamine-related close eyed hypnogogia that overtakes one when it is done in a quiet night-time setting. The phenomenological similarity of the hypnogogia to N,N-unspeakable is very satisfying since the energy level is much easier to handle.4

Later, he gushes, “I am personally delighted but perhaps it is a parent’s pride,” while offering Rick the opportunity to be among the first to sample the boon, which he ships under separate cover.

His correspondence conveys the mood that grips the pioneer navigating terra incognita, while at the same time recognizing the potential for economic sustainability: “I am cultivating Stro[pharia] on a scale with personal economical significance.” With a whiff of success in the air, a proposal is outlined. “If this little hobby proves lucrative,” he suggests transposing the operation to a rural English scene and repeating the process. More importantly, the profit from these labors will support a return to the Amazon. While he had not flinched from this objective, La Chorrera is no longer on the table. Plans for long residency in Colombia are disturbed by growing “visa restrictions and political uptightness.” To kick off in early 1976, the objective was now the Río Ucayali in Peru, a source of Banisteriopsis ruysbana, “the N,N-unspeakable containing yagé.”5

Terence had been manic that summer with the effort to prevent contamination, a scourge precluded by a “jolly inoculation chamber,” newly built. “Cruel indeed are the contaminants that haunt the Stropharia farmer, as cruel as the visions are delightful,” “Watty” learns. “But not unlike Anthony in the desert I have also to contend with the worldly allurement (all potentially my undoing) of mammon.” A “series of flues and deliriums” had been the result of his single-minded obsession:

Out of all this confusion and activity, like a distant peak rising out of the suspended dust of the common plain—and growing more clear each moment—is the idea of a return to the Amazon basin. An expedition around the first of the year to the Rio Ucayali drainage of Eastern Peru. For me, a crack at a second book and another deep look into the unspeakable. Naturally I am hoping that you will use the opportunity to put yourself on site and make it your Amazonian baptism.6

As finances remain an obstacle, he will need to return to the United States after a few months to “grow some more hongos so I can do it again.”7

By October 1975, Terry is out of the dark wood. Mail to Watty opens with its author embodying the wizard whose alchemical labors are pivotal for humankind’s cosmic return:

Like the breathless hush that accompanies any act of deep concentration the recent weeks have passed—a moment, many moments, an eternity. Now it is over, or over enough to speak of to one in a far distant country. Day and night the cookers roared, Watson. More than once I saw myself broken in health before the demands of the alchemical toil. Haunted by visions of contamination, arrest, or explosion I held to the mission revealed at the mandalic center of the oceans of vision . . . the grand plan for the symbiosis with man and through man and his eager hands the defeat of gravity and the return to the stars.8

Sufficient interest in the organic substrate for the pending transformation was also cultivated. “Now my humble part is played and the organism is well distributed through the Bay Area ecosystem, forming new liaisons with the local quantum electrodynamics folks and all the others it is interested to reach.” And so began the “consulting” work churning out a regular supply of mushrooms and selling grow kits and spore prints carried on art cards and shipped to buyers in sterile plastic envelopes from the newly minted operation, Lux Natura. Promoting the nascent business, and alluding to the brothers’ discovery of the La Chorrera P. cubensis strain that became known as “ANZ,” High Times reported in June 1976 that “there is a magical fungus among us.”9

Charged with hope, the communiqué to Watson continues: “There is a breath of change here that may be the faintest stirrings of a new order of things.” And we gain more than a hint of what, or indeed, who, assisted the restoration. “A dear woman friend, from Jerusalem days, Kat by name, and I shall within the month move to a pastoral setting somewhere in Hawaii, probably the slopes of Mauna Loa.”10 It had been over seven years since he’d first laid eyes on Harrison, whom he’d met as “a tide pool gazer and a solitary traveler” during his “opium and kabbala phase,” circumambulating the Mosque of Omar.11

A letter to Masayasu Takayama explains the transformation. Given the successful cultivation of the “little hongos” on a “vast scale,” enough money is made during the summer that Terence could travel wherever he wished. Affirming that he will shortly move to Hawaii, he humbly reports that “luck in time and life has brought a new woman into my life.” About Harrison, he is unreserved. “Beautiful and able to assuage my confusion and pain arising out of the way in which the last relationship ended so badly she is the new and definitely most important thing that is happening in my life. . . . She shines. And everyone feels very easy around her.” And with the start of the love affair, “I am slowly noticing that the world continues its unfoldment around me, it is nice to return to it and rediscover my place in it.”12

Harrison clarifies the situation herself. From “instructions” that they both receive in psychedelic states, they recognize that they are “supposed to be together.” A traveler, she is uncomfortable with the idea of settling down. In Terence, she saw a man driven toward the “transformation of the world” that had motivated her since her first psychedelic experience. It was “the combination of two minds and hearts looking toward that transformation and looking toward understanding it, expressing it, in order to help further it.” When she visited Nina Wise earlier that year, they had dropped in on the new bachelor. “It was electric to meet him again . . . but I still thought he was the weirdest person I’d ever met.” She wondered if it was even possible to have a child with him. “That sounds terrible,” she smiles, but she “couldn’t quite picture that part.” He had a mind, that she knew, but “was he even embodied?” Additionally, she wondered, “who was gonna pay the bills?”

After a week of visiting, Harrison returned to Catalina. Paying her a visit soon after, Wise carries a message from McKenna. He’d invited them both to join his next expedition. Playing that moment back in her mind, Harrison recalls the feeling. “That’s my life, I instantly realized. I’m going to have a child, at least one, with that person. The expedition is my life and he just invited me and that’s what’s going to happen. . . . I didn’t get a choice.”13

Harrison assented. This was the same month that the brothers figured out how to grow P. cubensis. McKenna started sending Harrison love letters with five grams of mushrooms attached to each one. She ate them all through that summer on her day off from waitressing. “Once a week, I took five grams of mushrooms, read his letters, programming myself for the future,” she said laughing.14 The mushroom would become integral to her life thereafter, and a key to their relationship. Throughout the spring and summer of 1975, Terence also takes five grams dried, or fifty grams fresh, “as often as I felt was prudent”—that is, about once every two weeks. Of this regime, he later reports: “The mushroom had made good its promise to send another partner.”15 By the end of the summer, they get together, and remain so for sixteen years.

From October 1975 to the new year, they rent a house amid the “twisted lava flows” on Kaʻū, Hawaii. There, they continue their romance, with each other and with the mushroom. They take five dried grams together every five days. The experience was, as McKenna relates, more than just shared hallucinations: “We would melt into each other’s minds in a Tantric climax.” Tripping one evening in late November, Terence is appalled to receive the unbidden idea that they could have a baby together. As the idea keeps coming up, he shares it with Kat. Loaded, they decide to walk outside under the open night sky. Cresting a knoll to greet the stars, he makes an internal inquiry: “If this is a good idea, give a sign.” At that moment, they witness a spectacular meteor burn. The mushroom speaks in his mind: “Such meteor burns occur but once in all time.” Hours later, still tripping, a low, grinding roar moves through the lava fields stretching for miles all around and beneath them. It is an earthquake that causes tidal waves and volcanic activity thirty miles away at Kīlauea Caldera. And so it was that they commit to a family and a life together.16

For Kat, other signs emerge—signs of their divergent approaches to tripping. With an abiding entitlement, Terence, she explains, was “more demanding of the universe” than herself. He had already received signs that he had a path, that he would make waves, become recognized, and therefore insisted that “you mushroom, you universe, you Hawaii, provide this for me. Make it show up. I want a sign, I want the thing. I want the woman. I want the piece of the puzzle to fall into place for me.” And he would, even then, while tripping, announce: “Show me. Show me . . . I insist.” Even then, she saw the hubris, and thought it troubling. She observed in these early stages that which later develops into an unbearable problem. “I just don’t think that you dance with it that way.”17

McKenna wanted to share his new mood with Watty, who is urged to meet him and his new friend in Iquitos around the New Year. “If you were eager to throw in on such a venture then I would begin to look toward it more eagerly.” On the other hand: “If there is not enough manpower to get together an Amazonian Expedition . . . then I shall probably just take my butterfly net and new friend and go on out to the Solomon Is.”18 The “manpower” shortage was an issue. But when he “tried to get out of” taking Harrison to the Amazon, she has none of it. “That’s my dowry. You promised me an expedition and we’re going on it!”19

By year’s end, the pressures on Watson mounted. A hand-drafted letter, dated December 13, 1975, was written in Kaʻū (see below). The effort to establish an “outdoor mushroom farm” on his “kīpuka home” proceeds, though it is too early to claim success. In fact, they would not find success growing mushrooms on Hawaii. Terence had firmed up his plans to mount an Amazonian expedition no later than the spring of ’76. A friend, Richard Brzustowicz, is on board for the trip, as is “the Lady Kat,” with their departure from Oakland to Bogotá set for March 1, 1976. He presses his old pal. “We are exploring options involving penetration of several geographically distinct areas: The Vaupes, the area around La Chorrera or perhaps the Rio Blanco, a tributary of the Rio Ucayali in Peru.” Terry is possessed by a manic mood that is the fate of the pioneer, the maverick, the unhinged. The message is impatient. Watson has one last chance to board the cosmic express train, departing soon.

It is no small aside that this message is penned on a Fritz Hugh Ludlow Memorial Library notecard with a reproduction of the front page of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, May 12, 1883, featuring C. Upham’s engraving “An Opium Den in Pell Street, Frequented by Working-Girls,” and entitled “A Growing Metropolitan Evil.” As the explanation on the card indicates, Thomas De Quincey’s wildly popular Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1822) “piqued worldwide literary interest in opium.”20 The motive for selecting such a medium for this communique grows more apparent. Not only is De Quincey regarded as a champion forebear in self-experimentation; the card (also mailed to other friends) implies how a literary work influenced an exotic drug’s appeal. Not only is the letter a last-ditch campaign to recruit Watson for the forthcoming Amazon venture, it is an effort to convince his pal to become the British outpost of a protean fungi farming fraternity, a pioneer in a potentially lucrative underground movement.

In the previous letter to Watson (October 5), McKenna was curious about the legal status of psilocybin in Britain, compared with the United States, where it was controlled as a Schedule I drug under the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970, thereby officially possessing a “high potential for abuse, no accredited medical use, and a lack of accepted safety.” If the lawscape was favorable there, perhaps the nascent grow operation could be transplanted to the Isles. And depending on Rick’s enthusiasm for the proposal, he was prepared to travel to the UK with Watson post-Amazon for a month or so to “do my thing.” Riding a high, Terence imagines the English underground favorable for getting his thing on. Had Graves not laid the groundwork long before when declaring (erroneously and without evidence) in the reprint of The White Goddess that his own experiences with psilocybin echoed the “ancient toadstool mysteries” of the Celtic bards?21 “Agent-hood in the starplot has made such delicious options doable,” wrote McKenna, “How can we get together out on the edge where the free electrons flow and know?”22

The response from Watson is not what was hoped for. Apparently, Rick hadn’t touched the mycelial gift. With possession of psilocybin (and psilocin) classed as illegal in the United Kingdom under the 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act, beshrooment was a furtive practice in Britain in 1975. In fact, the hallucinogenic properties of the liberty cap (Psilocybe semilanceata), the principal local source of psilocybin, were largely unknown. The immigrant is unprepared to be the mushroom man of Albion—but the lobbyist was having none of that:

I really need to have a long talk with you. Pity the Stropharia are so remote from Kew and your own situation is unconducive to taking them. Since last spring I have taken them about 20–30 times and it is the content of the visions they induce that now fascinate me and inform my motives, for hongos seem to do strange things to ones perception and understanding of time. “The holographic now” becomes more than mere figure of speech. Humanity’s long past and even longer future seems spread out before one, inviting inspection. Saucerian overtones and intimations of genetic magic long in the making further complicates the picture. We are in the grip of something that keeps its own motives carefully veiled—a singularity that haunts time and shapes events towards a purpose unseen, but . . . compelling.23

Visions received in multiple journeys over the previous six months confirm that the game is afoot, that Watson must down tools and get with the program. Growing reticence on Watson’s part is affirmed in the wake of the last pitch:

Frankly I need to have every mind that I respect at my side when the waters deepen again as they surely shall. No Ahab I, and not one so foolish to be unaware of the largess of compulsion and miscalculation. But I say to you now as I have said before, there is something out there in wild nature and the near future.24

Terry’s probation from the source had been lifted. With the resumption of transmissions from “the teacher,” he is once again in “close consultation with a cosmic agency of complex intent.”25 Downstream from La Chorrera, in the light of the gifts bestowed, he is drawn into a cosmic plot in which he is compelled to act as spokesperson. Correspondence with Watson in June 1975 illustrated further glimpses of the source. His nascent bloom appears to McKenna strange and incongruous flourishing so far from the Amazon basin. And yet the content of the visions induced are not context-dependent. “Here in Berkeley they are as saucerian, galactarian, and future orientated as they were in the Amazon,” Rick is informed. “The coherence of the visions remains their distinguishing feature—that it is not so much an experience of one’s own psyche but rather the experiencing of a place—or of many places. Far away places.”26 He is compelled to serve as an operative for those “far away places” for his remaining days.

Strange Attractor is out on September 30th, 2025. Get a 25% discount code if you order before August 1st here (US only).

Dennis J. McKenna, The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss: My Life with Terence McKenna (St. Cloud, MN: North Star Press of St. Cloud, 2012), 327

Terence McKenna, True Hallucinations: Being an Account of the Author’s Extraordinary Adventures in the Devil’s Paradise (New York: HarperCollins, 1994), 207. Though Terence’s memoir implies that he alone made the discovery, it was Dennis who landed on the technique.

Terence McKenna, “Down to Earth: Psilocybin and the UFOs,” 1979, 5 (McKenna papers, MSP 213, Box 3, Folder 3, Purdue Archives)

T. McKenna, letter to Rick Watson, June 25, 1975

T. McKenna, letter to Rick Watson, June 25, 1975

T. McKenna, letter to Rick Watson, August 10, 1975

T. McKenna, letter to Rick Watson, August 10, 1975

T. McKenna, letter to Rick Watson, October 5, 1975

Anonymous, “Bedroom, Bathroom, Mushroom: How to Keep a Perpetual Supply of Psilocybin in Your Own Home,” High Times, no. 10 (June 1976)

T. McKenna, letter to Rick Watson, October 5, 1975

T. McKenna, True Hallucinations, 215

T. McKenna, letter to Masayasu Takayama, October 12, 1975

Kathleen Harrison, interview by author, September 25, 2019

Kathleen Harrison, interview by author, September 25, 2019

T. McKenna, True Hallucinations, 207, 215

T. McKenna, True Hallucinations, 216, 217, 218; Terence McKenna, “Having Archaic and Eating It Too,” weekend workshop, New York Open Center, Spring St., New York City, October 13–14, 1990

Kathleen Harrison, Zoom interview by author, April 20, 2022

T. McKenna, letter to Rick Watson, October 5, 1975

Kathleen Harrison, interview by author, September 25, 2019

T. McKenna, letter to Rick Watson, December 13, 1975

Andy Letcher, Shroom: A Cultural History of the Magic Mushroom (London: Faber and Faber, 2006), 237

T. McKenna, letter to Rick Watson, October 5, 1975

T. McKenna, letter to Rick Watson, December 13, 1975

T. McKenna, letter to Rick Watson, December 13, 1975

T. McKenna, True Hallucinations, 207

T. McKenna, letter to Rick Watson, June 25, 1975

This is great! I was just thinking earlier this week that I'd like to read more about McKenna's life, and here it is!

More great writing on this Substack. Thank you.