This article by the author and lecturer PD Newman first appeared in Psychedelic Press XL: Folklore & Psychedelics.

The ‘Mississippian Ideological Interaction Sphere’ (MIIS) refers to a mysterious group of Indigenous Americans responsible for creating many of the enigmatic platform mounds and earthworks constructed in and around the Mississippi Valley—the awe-spiring remains of which are exhibited especially throughout the Southeastern landscape of North America.1

On top of the oft-found skeletal remains (both incinerated and intact) of what are believed to have been village chiefs and other significant tribal figures (in addition to, perhaps, their families, wives, slaves, and even human sacrifices), and in the vicinities around several of these sacred sites were found ancient artifacts bearing a number of caringly carved and painted abstract, anthropomorphic, and zoomorphic symbols.

These included ‘swirl crosses’ (swastika-like fylfot crosses), hunchbacked crones, winged serpents and serpents having antlers, underwater panthers (also having antlers), severed heads, fire-breathing skulls, disembodied hands with ‘eyes’ in their palms, and giant, intimidating raptors and moths. These pertain to what is now accepted by mainstream archaeology to be an early Native American model for the after-death journey—known colloquially as the ‘Path of Souls.’2

Central to the MIIS is a puzzling set of iconographic symbols, many of which appear to have been alien to the preceding Hopewell, Adena, and Poverty Point cultures. Executed largely in the Hemphill style unique to the Moundville archaeological site, the set of symbols comprising the Path of Souls cycle probably functioned in a manner analogous to that of books of the dead in other cultures.3 Although Moundville pottery differed from standard mortuary texts: the ‘Path of Souls’ ritual vessels are believed to have been both practical and interactive. Indeed, by virtue of their consecrated contents, these pieces were possessed of the power to invoke the supernatural depicted on (or fashioned as) the pot, projecting their drinker(s) directly into those Powers’ domains—various important points plotted along the Path of Souls.4

From culture to culture, both ancient and modern, the after-death journey is oftentimes envisaged as a heroic, postmortem rite of passage, replete with ordeals, trials, and tribulations which the struggling soul must overcome—challenges through which the dead must pass—if it is to reach its goal. In almost every case, this etheric excursion ultimately culminates in the final incorporation of the soul of the deceased into the realm of the ancestors or the domain of the divine. Of course, depending on regional variations, reincarnation or total oblivion may also sometimes be alternative outcomes.

Terminal trips of this sort have become familiar to us in the skeptical West through exotic, popularized magical spell and ritual mortuary texts, such as the misnomial Egyptian Book of the Dead, the equally misnamed Tibetan Book of the Dead, and via even more obscure lineages of mystical transmission, such as the controversial yet no less traditional teaching of the ‘Aerial Toll Houses’ in the Eastern Orthodox Christian Church. The Native American after-death journey known as the ‘Path of Souls’ constituted one such metaphysical mortuary map.

But, are ‘directions for the dead’ really all that this series of icons comprised? Yes and no. The answer is ‘yes’ insofar as the Path of Souls symbol set actually does qualify as a chart for the ‘checked-out’. Like a list of foreboding landmarks, the icons representing the Path of Souls are supposed to be followed sequentially—a spiritual schematic of sorts. However, the answer is also ‘no’ in that it probably wasn’t a journey reserved exclusively for the newly deceased.

In the form of an organized degree structure, appearing as certain sacred visualizations, ecstatic spirit journeys, and dramatic initiatory rites of passage, the Path of Souls was passed by priest, prince, and polity alike—that is, it was traipsed by both shaman and chief, as well as by members of an elite medicine sodality—while they were still alive.5 Well, not really alive—but not exactly dead either: suspended somewhere between the two, in a liminal, entranced state brought on by fasting, sleep deprivation, ritual action, body mutilation, and prolonged participation in drum and dance.

This profoundly significant ceremony would have taken the form of a formally-staged, ritualized mythodrama, specifically designed to pass an individual nominally through the very same trials expected to be encountered really on the Path of Souls. For that is precisely what the shamanic journey is understood to be—a magical death.6 Leaving his cumbersome corpse-like body behind, by the potency of the rite, the soul of the shaman was rendered free to roam the realms of the spirits and of the dead. Upon his return to the land of the living, anticipated boons of wisdom and power followed closely in the healer’s wake.

Although, as if that weren’t extreme enough, evidence suggests that these powerful trance induction techniques were not employed alone, but were in fact used by the Natives of the MIIS in conjunction with a number of different entheogenic teas and smoking blends.

While the infamous peyote cactus (Lophophora williamsii) and so-called ‘Desert’ tobacco (Nicotiana obtusifolia) will no doubt be familiar to most as important Southwestern Native sacraments, with the exception of tobacco, the Southeastern Indigenous use of the majority of the entheogenic plants discovered in and around a number of Mississippian sites may be largely unknown to the casual reader. Although, in this study, we will focus our attention on just one: Jimsonweed (Datura stramonium). But, before diving into the Datura directly, we’ll first need to make a short detour to what is now Tampa, Florida in the 1540s, where invading Spaniards first observed the indigenous imbibement of an interesting, invigorating, inky infusion—known as ‘Black Drink’.7

When DeSoto’s ship landed in what is presently the modern-day Sunshine State, it was noted that the Amerindians, every few days, were in the habit of boiling up a thick, black tea from the roasted leaves of a shrub resembling a cross between a holly bush and willow tree. To the surprise of the Spanish, upon assembling, the Natives would cheerfully drink, vomit, and drink again, leading later anthropologists to assume that the concoction simply functioned as an emetic and thus was a rite of purgation—and further resulting in an unfortunate classification by ethnobotanists, Ilex vomitoria: ‘the Ilex that makes one vomit’.

While it is certainly possessed of ample amounts of caffeine—indeed, closely related to South America’s yerba-maté, it is the only native source of caffeine in North America—yaupon holly (Ilex vomitoria) is not an emetic. I know this to be true from personal experience. Although, there is evidence that a number of other, often secretive, plants were regularly added to the ‘cassina’ brew, as it was called by the Ais, Timucua, and other Muskogean speakers.8

Traditionally imbibed out of giant whelk shell cups imported from the Gulf of Mexico, or from specially crafted pottery beakers, decorated on their faces with symbols of the Below World, the potation eventually became so popular among Mississippians that massive amounts of the plant had to be imported some sixteen-hundred kilometers inland, to the ancient city of Cahokia, where it was expected to sustain some several thousand regular drinkers.

A great many of these same shell cups were recovered from the city of Spiro in Oklahoma. After testing the residues in the cups and the beakers, researchers were not surprised to find traces of theobromine and ursolic acid—clear evidence of yaupon use. But, what they didn’t expect was that almost eighty percent of the vessels from Spiro tested positive for the presence of Jimsonweed alkaloids.9 The same is also true of curiously decorated ceramic bottles and ‘human head effigy pots’ recovered in and around the Central Arkansas River Valley10—as well as enigmatic, hunchbacked, crone-like effigy pots found secreted away in the Middle Cumberland region of Tennessee.11

This fortuitous floral discovery has helped to shed light on a rather puzzling recurring motif that pops up throughout the Mississippi Valley—and even further west, surprisingly, among Puebloan tribes such as the Zuni and the Mimbres or Anasazi.12 One of the bottles in question, housed at the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma,13 is decorated with a distinctive ‘jagged spiral’ pattern that is now widely recognized as a stylized depiction of the proboscis of a Sphinx or Hawk moth—Manduca sexta—a species that lays its eggs and feeds exclusively upon the intoxicating leaves and nectar of a pair of popular nightshades: tobacco and Jimsonweed.14

The larvae of this species are known as ‘tobacco hornworms’, due to the presence of a pointed red horn protruding from their bodies. Nicotine is generally poisonous to insects and animals. However, the tobacco hornworm is possessed of the remarkable ability to retain the drug within his body, unaffected by the toxin, which he is then able to eject out of his mouth at will, as a powerful defense mechanism. Ethnological evidence suggests that this defensive insectoid reaction may have been intentionally exploited by the Natives, independent of direct tobacco or Jimsonweed use. For instance, according to Navajo lore, the caterpillars themselves were employed in an entheogenic context. In his book, Navajo Legends, Irish-American ethnologist, Washington Matthews, related the following tale of an Indigenous ‘trial by fire’:

As the boys were about to enter the door they heard a voice whispering in their ears: “St! Look at the ground.” They looked down and beheld a spiny caterpillar called Wasekede, who, as they looked, spat out two blue spits on the ground. “Take each of you one of these,” said Wind, “and put it in your mouth, but do not swallow it.15

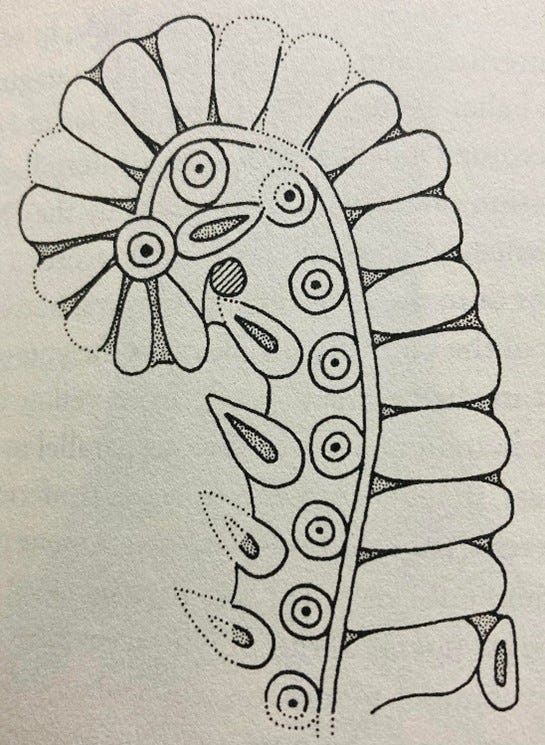

Just as with the juice of the tobacco plant, the protective nicotine-rich secretions of ‘Wasekede’ are not to be swallowed, but spat out. Immediately following this Wasekede episode, the boys go on to smoke ‘the tobacco [that] kills”—ostensibly, Jimsonweed—from a sacred calumet’.16 Images of this tobacco hornworm are preserved in a number of notable Mississippian relics, including a single exquisite crystal caterpillar effigy, and a stunning shell carving of this important insect in profile—both recovered from Spiro in Oklahoma. Perhaps the most significant example appears on the Middle Tennessee ‘Thurston Tablet’, found at or near the Castalian Springs Mounds in the late 1800s and currently on display at the Tennessee State Museum.17

Insofar as the alkaloids consumed during the insect’s larval stage are retained within the bodies of the developing pupae, and finally within the constitution of the moths themselves—making them a bitter punishment for any animal unlucky enough to try to eat them—it is possible that the Manduca sexta itself is psychoactive. Known to archaeologists by the pop cultural epithets, ‘Mothra’ and ‘Mothman’, this lepidopterous non-human entity really does get around, appearing far and wide in the iconography of various Amerindian traditions.

For instance, alongside Datura flower ‘pinwheels’, he shows up painted on the stone walls of Pinwheel Cave in Southern California (where spent Datura quids were actually recovered),18 anthropomorphized in kiva paintings from Pottery Mound in New Mexico, pars pro toto on negative painted bottles found in Scott County, Arkansas, carved out of shell gorgets from Etowah, Georgia, and etched, ‘phantasmagorically’ into a shale palette from Moundville, Alabama—among still other closely related locations.19 Notably, for a culture lacking in written language, these icons served a function similar to that of labels on prescription medication bottles in the metamodern West, indicating to the viewer the precise ‘medicine broth’ that the particular vessel would have likely contained.20