The following article by acid historian Andy Roberts first appeared in the Psychedelic Press print journal, issue XL. A few copies of this limited, special edition journal on folklore and psychedelics are still available to buy here.

‘LSD is a psychedelic drug which occasionally causes psychotic behaviour in people who have NOT taken it.’1

Some elements of psychedelic folklore are relatively easy to unravel. For instance, the belief that towns, cities or even a country’s entire population can be rendered helpless by introducing LSD into the public water supply can be scientifically refuted.2 And the popular lysergic legend that Francis Crick’s alleged use of LSD played a key role in helping him to discover the DNA double-helix crumbles when the facts are closely examined.3

Yet these tales continue to circulate, meme-like, on the internet and in the media as ‘truths’, demonstrating how difficult it is to convince people they are legends even when irrefutable evidence is presented. Determining the genesis of the Blue Star Tattoo legend and untangling how and why it has spread and persisted for decades presents a much more difficult challenge though as this particular psychedelic folklore motif does have some basis in reality.

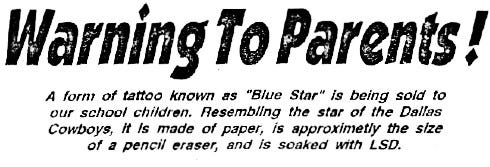

Although this essay deals specifically with the UK iteration of the legend it is first necessary to give a brief summary of its genesis and spread in the USA. During the early 1980s, newspapers, TV stations, education, health boards, police stations and other public facing organizations began to receive a slew of unusual letters and faxes. These alarming missives claimed school children were being given or sold small ‘tattoos’ or ‘transfers’ featuring attractive and colourful images such as blue stars, red pyramids, and well-known cartoon characters. The kicker was that these ‘tattoos’ were allegedly soaked in LSD!

The legend claimed that when the unwitting child applied one to their skin, instead of sporting a cool temporary tattoo with which to impress friends or parents, they would be plunged into a powerful and hellish psychedelic experience which would lead to psychological or physical damage, addiction or death. The inference was that children were targeted and exploited due to their vulnerability and would become addicted to LSD by using these ‘tattoos’, thus introducing them to a lifetime of drug use and boosting the dealers’ customer base. The legend became known as the Blue Star Tattoo because a small blue star was one of the first images said to be on the ‘tattoos’.4

At face value the Blue Star Tattoo scare is the stuff of every parent’s worst nightmare. Or it would be, if it was true. But it wasn’t, it was an urban legend, a piece of psychedelic folklore carefully created for the post-hippie world of the 1980s and beyond. As the American and European iteration of the legend has been covered by notable folklorists including Jan Harold Brunvand I will concentrate on the British version, identifying its genesis and spread and examining what truth there is behind its lurid claims.

By examining the available drug literature and scouring several newspaper archives, the first British example of the legend I could find occurs in March 1981, soon after the appearance of the legend in America and continental Europe. Schools throughout the Black Country area of the Midlands began to receive letters and faxes, ostensibly from the police, warning teachers and parents that children may be offered ‘LSD-coated cartoon stickers’. West Midlands Drug Squad officers immediately denied any knowledge of the letters, claiming:

Stories about these LSD-coated stickers started some time ago. They were supposed to have originated from somewhere on the continent, but we looked into it and found no evidence of any such stickers.5

Although the method of delivery was now ‘stickers’ rather than ‘tattoos’, the basic legend was near identical to its American and European counterparts. The police refuted it and made it clear there was nothing behind the scare letters. A simple, but effective hoax. Nothing to see, move along now.

But for some reason, as was the case in America, the legend refused to die and the British print media slavishly and with minimal attempt at investigation or analysis repeated the story throughout the 80s. Terminology used in the British media changed slightly from the American iteration of the legend and whilst ‘tattoo’ was occasionally mentioned ‘transfer’ and ‘stamp’ became the prevalent name. Thus, ‘LSD Peril’, ‘LSD on Cartoon Ploy’, ‘Drug Warning Over Transfers’, ‘LSD stamps peril’, ‘Peril of the LSD on Cartoon Stamps’ and many other permutations of those words were repeated frequently in newspapers across Britain. Yet, like all the best illusions, the truth behind the Blue Star Tattoo legend was in plain sight from its first appearance but was ignored for reasons I will discuss later.

Despite the legend being frequently discredited by the police numerous times in the 1990s it continued to grow, spreading widely across Britain. In my files I have over 150 very different news clippings pertaining to the legend. This may not sound like many, but each of those stories was repeated numerous times, as the result of press releases or local and regional newspapers picking up on reports in the nationals and re-publishing them, resulting in the legend appearing thousands of times in the British media. Often the same news report would confusingly state the legend both as a lurid truth by journalists whilst being simultaneously debunked by the police. This ambiguity and lack of certainty was a crucial enabling factor in facilitating the spread and mutation of the legend!

A journalist writing in a 1990 edition of the Herts & Essex Observer reported on one letter—purporting to originate with the ‘Essex County Constabulary’ (even though no such organization existed; since 1975 they had been simply called ‘Essex Police’)—noting that ‘They say the tattoos are laced with LSD and poisonous strychnine which can be absorbed through the skin.’ Inspector Roger Howe of Essex Police wearily responded, ‘This warning has become quite widespread. It is a hoax. We’re not aware of any seizures of LSD in tattoo form in the UK’.6 Howe’s denial was disingenuous though as he would have known, as we will see, just what the ‘tattoos’ actually were.

The reference to strychnine, a far more dangerous drug than LSD, being added to the mythical LSD-soaked stamps was one of the main mutations to the legend and soon led to a question in the Houses of Parliament. Sir Michael McNair-Wilson asked, ‘The Secretary of State for the Home Department what action his Department and the police are taking to discover the source of self-adhesive stickers laced with LSD and strychnine which are being offered to children; and whether anybody has yet been apprehended for offering these substances?’ Peter Lloyd, on behalf of the Government, responded:

I understand from the national drugs intelligence unit and the police that they have not been able to find any evidence whatsoever to support such claims that such stickers exist. In the absence of such evidence, the police here and in other countries believe that circular letters claiming that such stickers are being offered to children are a hoax, although they remain ready to examine any evidence which is put to them.7

Claims that LSD is often contaminated with strychnine is yet another psychedelic urban legend and introducing this element to the Blue Star Tattoo legend added another layer of danger with which to worry parents and the authorities. Since the 1960s, some LSD users have claimed painful reactions to LSD, such as stiff muscles and joints, were caused by the addition of strychnine, and it quickly became a popular lysergic legend.

This piece of psychedelic folklore appears to have originated from a comment made by Albert Hofmann, the discoverer of LSD. Writing in LSD My Problem Child, Hofmann noted that strychnine had been found, once, in a sample of LSD in powder.8 Other counterculture legends including psychoactive drug chemist Alexander Shulgin and Bruce Eisner also determined the addition of strychnine to LSD to be rumour rather than fact. Despite there being no evidence to support this rumour strychnine had now become attached to the Blue Star Tattoo legend in Britain.

Absence of evidence is, of course, not evidence of absence. But the Blue Star Tattoo legend was beginning to come under examination by sceptics. Writing in Fortean Times Paul Sieveking noted, ‘In 1991, when the story was already over a decade old, I wrote that, “the Blue Star acid transfer story is a bit like a vampire; no matter how many times you cut it down it rises again to scare the pants off another generation of ill-informed parents”’.9 Perceptive as he was regarding the folkloric nature of the Blue Star legend Sieveking, despite his counter culture background, he apparently failed to realize what the source of the legend was.

It should be obvious the Blue Star Tattoo legend, whatever its origin, is a variant of the chain letter, a message exhorting the recipient to copy and send the letter to as many people as possible. The content of a chain letter invariably consists of emotionally manipulative stories or promises some form of reward to ensure the receiver doesn’t break the chain, suggesting that ‘bad luck’ of some kind will befall those who do. Several of the Blue Star communiques actively encouraged the recipients to copy and spread the legend, such as the piece in a Birmingham paper in which the recipients were actively encouraged to ‘Reproduce this article and circulate it within the community and workplace.’10

Unlike most chain letters though, no negative consequence from failing to pass on the letter was stated overtly but the clear inference was that by not spreading the legend children and young people’s lives would be at risk. The identities of those who churned out the Blue Star Tattoo communiques were never discovered (in Britain or elsewhere) and their appearance began to tail off toward the end of the 1990s. I have only been able to find a handful of examples from Britain between 2000–2023 which I believe to be because of the rise of the internet and social media.

It would be easy to sum up and dismiss the Blue Star Tattoo legend as being a variant or mutation of one of the thousands of chain letters that have existed since 1935 when the first was identified. But I think the legend can be traced a specific point in time.

Let’s go back to the early 1980s when the Blue Star Tattoo legend first appeared. LSD was still available but the psychedelic decades of the 60s and 70s were over and the use of harder, more destructive drugs such as heroin and cocaine was on the rise. Many countries were initiating substance abuse prevention programs, several aimed at children and in 1981 Nancy Reagan (the then US president’s wife) became heavily involved in the anti-drug movement and was quoted as saying ‘Understanding what drugs can do to your children, understanding peer pressure and understanding why they turn to drugs is … the first step in solving the problem.’11 And that, in a nutshell was exactly what the Blue Star communications were claiming about the LSD tattoos.

Before revealing the reality behind the Blue Star Tattoo legend it’s worth examining the claims made by its anonymous creators and popularizers. Did the tattoos exist in the form the legend claimed? No, not one instance of an LSD-laced tattoo, transfer, sticker or other form of paper was ever found in the possession of a child. Nor was anyone ever arrested and charged with giving or selling a tattoo to a child or arrested for sending the Blue Star chain letters.

Furthermore, the claim that the tattoos were being given or sold cheaply to children is risible. No drug dealer would have any interest in giving LSD to a young child because there is no fiscal motivation to do so, children not being known for having disposable income with which to buy drugs of any kind. The LSD chain letters’ claim that the tattoos would get children addicted to LSD is ridiculous because LSD is not addictive. Quite the reverse in fact: the human body quickly builds tolerance to LSD and increasingly-large doses must be consumed to achieve the same effect.

And despite the claims that the tattoos could result in death or serious injury from the effects of LSD, it is widely considered to be physiologically safe, and very few people have ever died or suffered physical injury from its use. Of course, there could be the possibility of psychological damage from unwitting use of LSD, but as the ‘tattoos’ didn’t exist in the form claimed by the legend, there was no chance of that happening either.

But let’s humour the legend for a moment and imagine LSD-soaked tattoos did exist and had escaped the clutches of the law, would they have the claimed effect if placed on the skin? Det. Chief Supt. Derek Todd of the Central Drugs Squad stated, ‘Even if LSD was in the tattoo, it would not absorb through the skin, our laboratories would tell us that.’12 During research for this essay I asked a number of people who have been heavily involved in LSD manufacturing or in handling large quantities of LSD, and the consensus of opinion is that LSD placed directly on skin would have no effect whatsoever. Even Albert Hofmann’s claim that his first, involuntary, experience with LSD in 1943 came from him accidentally getting it on his skin is being challenged.

So, if the basic premise of the Blue Star Tattoo legend is false, where did it spring from? One crucial factor that folklorists appear to have overlooked is that the genesis of the Blue Star Legend began at the same time as the huge increase in availability of a particular form of LSD delivery system known as ‘blotter acid’: sheets of blotting or other porous paper soaked in LSD which are then perforated into tiny squares. Does that sound familiar?