The link between memory and the psychedelic experience has always fascinated me. Whereas short-acting, acutely transformative substances like DMT tend to bring about an all-encompassing (albeit otherworldly) presence, mid-range doses of psilocybin and LSD—and even (perhaps especially) ketamine—thread a fresh layer of translucence through the veil between past and present. For good or for bad, they blend into one another in myriad ways.

Sometimes this meshed sense of time is barely yet eerily perceptible, a haunting or deep recollection making itself known through the environment, while other times it smashes you in the face like a bolt from the blue, as if you find yourself simultaneously in two places at once. This interplay with aspects of time is, out in the field, precisely a playfulness—one with joys and challenges. It is also, in many regards, a fundamental premise in psychedelic therapy that stretches back to its earliest development.

In literary form, the most famous example of recovered memory from the 1960s is Myself and I (1962) by Constance A Newland (a pseudonym for Thelma Moss). Her account of taking LSD with Freudian and Jungian therapists is a psychosexual narrative that culminates in recovering the memory of a painful enema, which she then connects with her present issues around sex, thereby resolving them. Today her health issues would be described in terms of trauma—and trauma might be understood as the shadow side of the interplay of time.

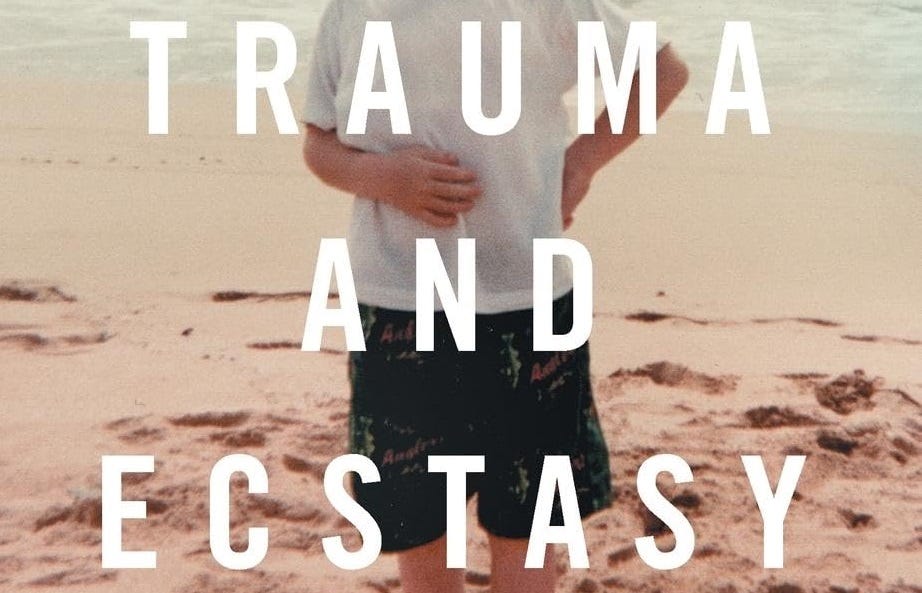

Trauma and Ecstasy: How Psychedelics Made My Life Worth Living (2024) by Alex Abraham is an account of undergoing underground psychedelic therapy in the renaissance years which follows a similar, although much more harrowing, journey than Newland’s. Abraham’s therapeutic journey is spliced together with his reconstructed autobiography as his memory of childhood sexual abuse is brought back to light and then pieced back together through the narrative.

The story begins with Abraham biking around the Netherlands in his mid-twenties. He develops a discomforting feeling around his perineum area. What begins, he believes, as an injury caused by biking develops into life-changing symptoms, with erectile dysfunction, an inability to control his bladder and chronic pain. Unable to develop relationships and his confidence crumbling, his life takes a turn for the worse, as numerous doctors and therapists are unable to relieve his symptoms.

Slowly turned onto psychedelics through the desperation of his situation and the writings and podcast of Tucker Max, Abraham sets out to find an MDMA therapist in New York City, and begins to unravel the psychological reasons for his physical trauma. What follows is him trying several medicine-based therapists alongside talking therapy. This shift of therapist is in part because of moving to Austin, Texas, but also in trying to find the right interpersonal dynamics.

As his sessions progress, Abraham’s longstanding psychological defences weaken, resulting in more fractious dynamics with his therapists alongside more extreme reactions to the drugs. He eventually settles with ‘Katrina’ who is bold enough to hold space for him, and it is she who helps him root out the long-blocked memory that was the foundation of his physical trauma—the serious sexual abuse he received at the hands of his music teacher over several years in grade school.

Through the use of MDMA, and later psilocybin and LSD, Abraham’s memory begins to reconstruct itself. The autobiographical chapters dealing with his recovered memory of sexual abuse are, to say the least, distressful and difficult to read (notwithstanding the compelling writing style). Questions about how his own family and the school missed the signs trouble Abraham in his journey as much as the reader, and says something implicit about how a reality must be recognized to be remembered. Without consensus such horrific experiences must more easily be submerged below consciousness.

By the book’s end, which covers not only Abraham’s continuing therapeutic journey, and the emotional and relational steps he takes with those around him, but also his attempts to bring his abuse to the attention of the authorities, he can be said to have taken crucial steps. Yet the physical symptoms of his trauma continue, albeit eased. While his life has more purpose and focus, he says; ‘I don’t believe I will ever be fully “healed,” in the same way I will never be perfect.’ There is, I believe, some great wisdom in this observation.

Reading Trauma and Ecstasy made me realise the interplay and meshing of past and present is as much a feature of the psychedelic experience as it is trauma. When the balance of time is misaligned, our present is haunted not only psychologically, but potentially physically too. We may find ourselves forced into trying to live in two places at once. Conversely, in contrast to their ability to creatively produce precisely this type of divided experience, when skilfully employed psychedelics may also reconcile such matters and lead our way back to an integrated state.

What an amazing story! Join us as Colorado Psychedelic Society will be hosting a talk with Alex Abraham on Feb 19: Join me at Trauma & Ecstasy: A Talk with Alex Abraham https://meetu.ps/e/NNlPL/qzkSC/i

Wood loving Psilocybe:Azurescens specifically, can pull up deep buried memories, some so far down in the well of consciousness(sub & waking) that the imagery become somatic, neural symbols mirrored up inverted alien waves pulled over your eyelids by lunar magnetism.