When I was an undergraduate at Berkeley in the late 1980s, it was not uncommon to see Thom Gunn strolling down the halls of the third floor of Wheeler Hall. The British poet taught Creative Writing and Poetry at UC Berkeley for several decades and it was easy to spot him in his trademark leather jacket, jeans, and boots. On some occasions, Gunn’s bellowing laugh could be heard echoing through the corridors.

When I saw Gunn in Wheeler, I would greet him and he would smile back, but I was too afraid to take his creative writing class. Despite his cheerful demeanor, Gunn was just too intimidating—someone who featured in the Norton Anthology of British Literature alongside Ted Hughes and Philip Larkin. After I left Berkeley, I followed his career from a distance. His fame would rise again in the 1990s with the publication of The Man with the Night Sweats (1992) which chronicled the ravages of AIDS. Although Gunn remained HIV negative throughout the AIDS crisis, I was shocked to learn that he died from ‘acute poly-substance abuse’ in 2004. How did Gunn go from being a famous poet to someone doing some very dodgy drugs at the age of 74?

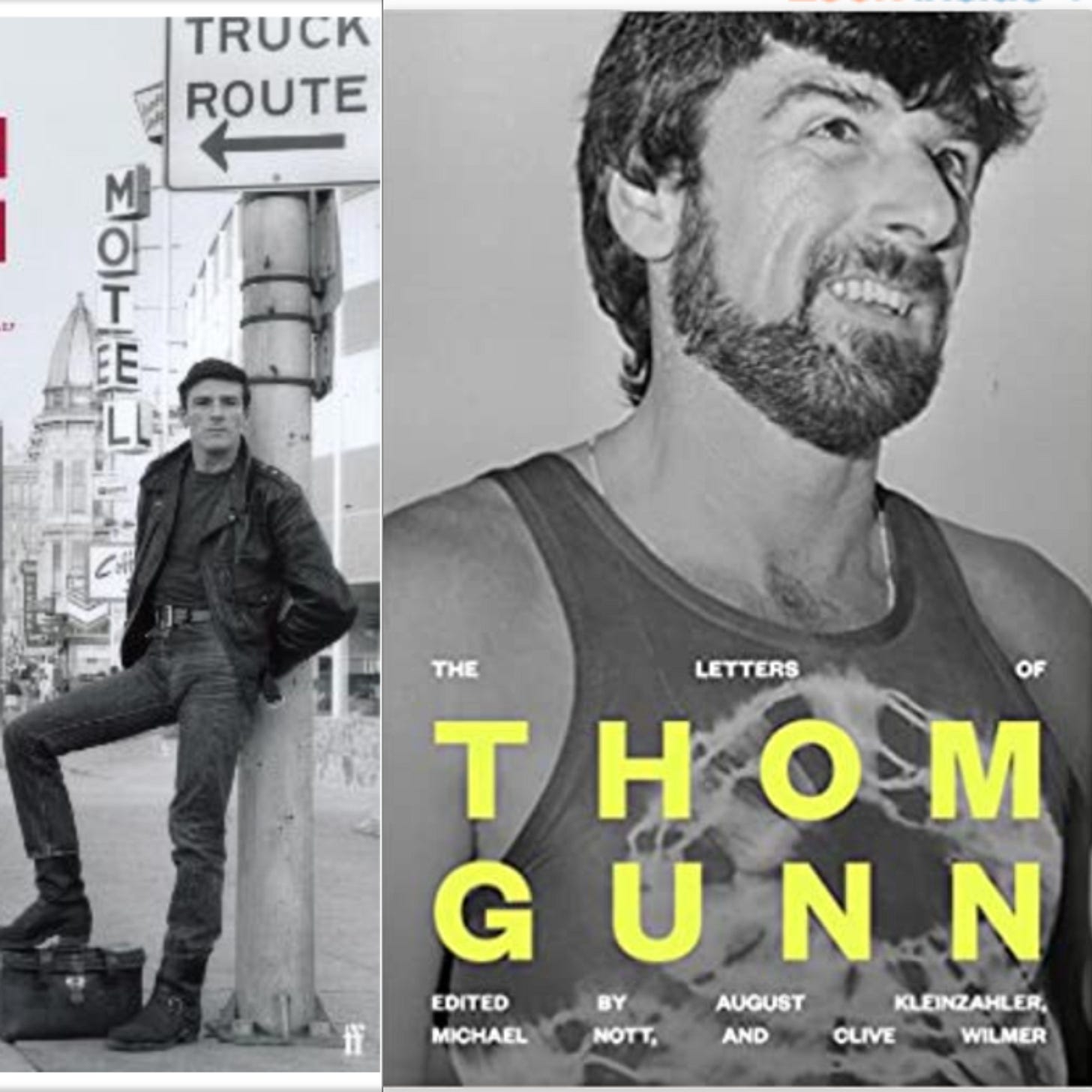

As an intimate window into the British poet’s personal life and creative process, the recent publication of The Letters of Thom Gunn (2022) does provide some answers. Gunn’s book of letters comes at the tail-end of the genre of letter writing. With the arrival of email in the 1990s, the act of writing a physical letter became far less common and eventually obsolete. Fortunately however, Gunn never gave up writing letters; even writing long, introspective ones during the last year of his life.

To be honest, I am generally not someone who rushes out to buy volumes of letters, but this massive volume—some 800 pages—is truly the exception. Gunn is a gifted letter writer: a witty raconteur with a lively sense of humor. In many letters, Gunn frequently assesses the authors he is reading, his creative process, his fallow periods, and where he is at in his life, philosophically and romantically. He is candid about his shortcomings, but is also careful never to bore his readers, thus he frequently catalogues his sexual escapades and wonderous drug trips for their entertainment.

I always knew that Gunn had a special attraction for psychedelics, but now we have a behind the scenes view of how they actually shook up and transformed his poetry. For Gunn, psychedelics were important because they pried open the self and revealed forms of self-knowledge that were often closed off to his sober-minded self.

The most exciting part of the letters for me is how they reveal a tension that was always present in Gunn’s life and work. On one hand, there is the domestic sphere, Gunn’s interest in cooking and gardening and the mundane affairs of his queer housemates. Gunn’s teaching career is closely aligned with the domestic sphere because it keeps him grounded and out of trouble. On the other hand, there is the desire to be a poet maudit who is attracted to Dionysian pursuits. For Gunn, there are chiefly two roads of excess: sex and drugs. These pursuits are not merely recreational activities, they are at the core of his identity and they are frequently represented in his poetry.

In the mid-1950s, Gunn had settled in the Bay Area and slowly became immersed in the counterculture of the 1960s, which featured such literary luminaries as Ken Kesey and Allen Ginsberg. In 1966, Gunn describes feeling the magnetic pull of LSD: ‘I am taking LSD for the first time on Sunday. I am about the last of my friends to take it, but I didn’t think it would mix with those three damn lectures a week’ (199). At this point in his career, Gunn is careful to separate work and pleasure. Gunn welcomes the LSD experience because he was at a crossroads in his life and his career as a poet.

His then most recent book of poems, Touch (1967), disappointed some reviewers and in some letters even the poet himself.[1] In one letter, to Tony White, a confidant from his Cambridge years, Gunn makes a startling confession: ‘I think during the past year [1965] I have reached a real indifference to being a career poet. I honestly have no intention of being a Great Poet’ (195).

During that same year, Gunn decides to give up his tenured position at UC Berkeley, something rarely done in academia. His career dilemma was not merely a case of writer’s block; he felt the need to alter his life in some dramatic fashion. At this pivotal moment, psychedelics are waiting for Gunn and they offer him a mid-career voyage into the unknown and poetic self-reinvention.

The tensions in Gunn’s personal life and work are perhaps best understood when we apply the Nietzschean notions of the Apollonian and the Dionysian to his poetry. On one hand, he was a disciplined Apollonian poet who valued order and structure and possessed a fidelity to meter and rhyme. Clive Wilmer, a close friend and scholar of Gunn’s work, perceptively argues that ‘despite the appearance of bohemian spontaneity, [Gunn] was an orderly gentleman, almost obsessively so—and he had very clear ideas of what he wanted his work to be.’ Some of Gunn’s poetic contemporaries felt that Gunn’s work was stuffy and old fashioned because he rarely wrote in free verse and he had contempt for the confessional mode.

If Gunn’s emphasis on rhyme and meter conveyed the Apollonian side of his personality, the subject matter of many of his poems revealed his Dionysian interest in gay sex and mind-altering drugs. Gunn’s carnal pursuits and erotic adventures are grouped under the phrase ‘the New Jerusalem’. Gunn used the Blakean phrase to evoke his participation in the making of a sexual utopia.[2] In one of Gunn’s later poems, he writes, ‘The 1970s/ There are many different varieties of New Jerusalem,/ Political, pharmaceutical—I’ve visited most of them./ But of all the embodiments ever built, I return to one, for the Sexual New Jerusalem was by far the greatest fun.”

Throughout his career, Gunn remains a fascinating contradiction: a traditional poet with one foot in the past and another foot in the transgressive underworld of sex and psychedelics. After reading all of Gunn’s letters, I am not sure that these contradictions in his poetics and his personal life are ever ironed out.

In the 1960s, one of Gunn’s close friends accused him of following the latest fashion—'Sartre one year acid the next’—but Gunn didn’t seem to mind the accusation that he was a trend follower. For the Anglo-American poet, psychedelics offered a new way of seeing: ‘With drugs you get glimpses, but only glimpses, of other ways of knowing, and of forces beyond you, but I don’t think any person or system has ever been able to name those ways of knowing or those forces’ (244). In one interview, Gunn noted, ‘I liked LSD because it broke down categories…by your middle-30s, you can get a big smug, and the 60s—and by this I mean the drugs, the concerts in [Golden Gate] park, all of it turned over my assumptions and delayed my middle age smugness a little’ (Lesser 4).

In one remarkable letter to Tony Tanner in 1969, Gunn vividly describes his most powerful and memorable LSD Trip. This experience would be captured in Gunn’s psychedelic poem, ‘At the Centre’ (1971). Gunn had taken some very strong LSD with close friend Dan Doody. After ingesting, the pair find themselves on a San Francisco rooftop gazing at an enormous neon sign for the Hamm’s Brewery in the distance.

In ‘At the Centre,’ Gunn writes,

Above Hamm’s Brewery, a huge blond glass

Filling as its component lights are lit.

You cannot keep them. Blinking line by line

They brim beyond the scaffold they replace.

What is this steady pouring that

Oh, wonder

The blue line bleeds and on the gold one draws.

Currents of image widen, braid and blend

—Pouring in cascade over me and under—

To one all-river. Fleet it does not pause,

The sinewy flux pours without start or end.

For Gunn, the image of an enormous ‘blond glass’ overflowing into a ‘one all-river’ becomes a potent symbol for human life itself. The speaker becomes a vessel or container that is overflowing with the life-force. As in many LSD trips, Gunn’s unconscious mind seizes on a potent image (the perpetually overflowing glass) that triggers an ego death: the point at which the powerful image/metaphor replaces the speaker’s actual ego. The speaker becomes the overflowing glass for an unspecified amount of time during the trip. ‘At the Centre’ ends with the speaker returning to his sober self, but the trip is not entirely over:

Later, downstairs and at the kitchen table

I look round at my friends. Through light we move

Like foam…

Hostages from the pouring we are of.

The faces are as bright now as fresh snow.

Gunn captures the afterglow of the trip and the effervescent transformation into human ‘foam’. Although ‘At the Center’ ends with a reference to ‘fresh snow’, Gunn’s letter to Tanner also reveals there was another episode that was not represented in his poem.

While on the rooftop with the Hamms brewery sign in the distance, Gunn writes:

‘I had a conversation with God. It may seem strange to somebody brought up completely without religion to do such a thing, but by God I meant…It, the source of the universe, etc. I can tell you I put some pretty challenging propositions to God, and he gave me no answer. Of course, I didn’t see him because it was not a human shaped figure I was speaking with’ (240).

As Gunn is speaking with God, he begins to ask existential questions that perhaps refer to his recent experience of ego death: ‘At one point, I [Gunn] remarks, [w]ell if I don’t have an identity and I don’t have love, what is there? And he said, “honor…by honoring oneself one can honor other people.” And then, click the peak was over.” Gunn describes those two hours as ‘the most interesting in my life.’ He adds,

‘this was a trip different in kind from any other, and I still feel remarkably cleaned-brained from it. I was at The Stud[3] for a while later in the evening, and I noticed something I’ve noticed before when I am coming down from a trip: one seems to other people the most beautiful one has ever been. Partly, I think, because one has an air of self-sufficiency, partly because one’s pupils are still enlarged and look full of wonder’ (240).

I enjoyed reading Gunn’s letters because they often contain confessional gems that illuminate Gunn’s understanding of the psychedelic experience and its unique value to him; they also fill in the elliptical gaps that are often present in many of his poems.

In same remarkable letter to Tanner, Gunn also argues that LSD is useful in the sense that it radically alters one’s identity: ‘one thing it does (& grass too, to a much less degree) is to present as possible still the choices one had thought were settled long ago. Which is why confirmed homosexuals can become bisexual (for a time, anyway). Not that I see that as likely to happen to me.’ Gunn’s point here is to account for the protean nature of the LSD experience and its capacity to shatter and remake one’s identity (240).

Gunn was well aware that writing poetry about LSD experiences was a tricky enterprise because the poem might drift into the realm of cliché or hyperbolic expression. Gunn’s solution for this problem was to embrace rhyme and meter to provide an anchor for the poet:

‘Meter seemed to be the proper form for the LSD-related poems…[t]he acid trip is unstructured, it opens you up to countless possibilities, you hanker after the infinite. The only way I could give myself any control over the presentation of these experiences, and so could be true to them, was by trying to render the infinite through the finite, the unstructured through the structured. Otherwise there was the danger of the experience’s becoming so distended that it would simply unravel like fog before the wind in the unpremeditated movement of the free verse’ (The Occasions of Poetry 182).

Gunn’s poetic strategy for writing about the LSD experience is often cited in books about psychedelic writing. When Gunn published Moly (1971), a book that contained several LSD influenced poems, he was aware of the risk involved: ‘the reviews [of Moly] will be something. I mean, it’s almost as if I am inviting them to discuss acid and homosexuality rather than the quality of the poems’ (269). For Gunn, boldness and self-acceptance were part and parcel of the LSD experience.

Although Gunn embraces LSD as liberating in the sense that it enables the poet to discover a new sensibility and mindset, his critics have often frowned on his willingness to write about his psychedelics experiences. In Gunn criticism, there is a tendency to favor the eulogistic poems from The Man with the Night Sweats over the LSD themed poems from the 1960s and 1970s. Hilton Als, a reviewer for the New Yorker, argues that Gunn’s…

‘1971 collection, Moly, which was inspired by his experimentation with drugs—“something is taking place./Horns bud bright in my hair./ My feet are turning hoof./ And father see my face”—put me at further remove: drugs don’t make you transcendent; they create false narratives about vision, power’ (60).

In this case, Als misreads the speaker’s imagery. Gunn was describing the changes that occur in puberty rather than the effects of a drug trip. Moreover, Als’s critique of Gunn also implies that all drug experiences can be reduced to one unified narrative. In contrast, Gunn’s psychedelic poems in Moly are expansive and written in Gunn’s elliptical style and they focus on the speaker’s quest for enlightenment and revelation. For me, the psychedelic poems in Moly are a crucial chapter in Gunn’s body of work because they provide a necessary prelude to the loss and despair that are captured in The Man with Night Sweats.

Although Gunn’s fondness for psychedelics never waivers, he eventually gets into harder drugs. Methamphetamines were often used to enhance Gunn’s sexual experiences. Gunn’s growing addiction to methamphetamines even creeps in to one of his later poems:

I am sixty-seven,

and have high blood pressure,

And probably shouldn’t

be doing speed at all.

Gunn retired from Berkeley’s English Department in 1999 and the letters reveal that retirement did not treat him so well.

During the last five years of his life, Gunn experimented with harder drugs (PCP, Speed, Crystal Meth, and heroin) that could enhance his sexual experiences. He increasingly becomes attracted to homeless young gay men who were also addicts. During this period, Gunn wrote less and less poetry and even told his friend Clive Wilmer, ‘I have no juice.’ Teaching used to keep Gunn grounded, but now he was almost completely unmoored. Dionysian pleasures became the central goal of this life. Mike Kitay, Gunn’s lifelong partner noted that Gunn’s sexual drive never seemed to wane as he aged: ‘What was that?...It seemed to me something beyond libido. There is something there that is bottomless, that no amount can fill up’ (Guthmann 8). August Kleinzhaler, a poet and a close friend who lived across the street from Gunn, commented on the British poet’s behavior during the last five years of his life:

‘I think he got despondent about not being able to be a sexual buccaneer. Not being attractive, or having the stamina…Thom very much disliked, perhaps feared, the idea of slipping into decrepitude, and lived the last few years of his life accordingly. He got bored upon retiring; that along with his depression about not writing and ageing, resulted in his greater intake of alcohol and drugs’ (Guthmann 10).

The letters clearly foreshadow Gunn’s path of self-destruction. They reveal his idolization of youth and his obsessive pursuit of speed enhanced sex. Gunn’s housemates were aware that the famous poet was courting death. They even tried to intervene on a few occasions, but to no avail. Gunn is well aware that his intake of methamphetamines was dangerous for an elderly man with high blood pressure. However, the letters often reveal Gunn frequently boasting about his young lovers and the risky sex that he can’t resist.

On April 10th 2004, Gunn’s housemates notice that nobody has seen Thom all day. When they opened the door to his upstairs room, the television was blaring and the poet was lying on the floor with his mouth agape. Mouth to mouth resuscitation was attempted, but it was futile because the poet had been dead for hours.[4] The cause of death was a heart attack induced by ‘acute poly-substance abuse’. Traces of alcohol, methamphetamines, and heroin were found in his bloodstream. Gunn’s death was not a willed suicide in the dramatic fashion of Hunter S. Thompson or Hart Crane, but it was certainly not a surprise to his inner circle of friends because the poet had been courting death for several years.

In a biographical essay entitled ‘My Life Up to Now’ (1979), Gunn remarks, that ‘it is no longer fashionable to praise LSD, but I have no doubt at all that it has been of the utmost importance to me, both as a man and as a poet’ (The Occasions of Poetry 182). Gunn never disavowed psychedelics nor did he ever conceal his fascination with them. Although Gunn’s end may seem a tragic pronouncement on his life choices, I believe that young readers and future generations will be attracted to his poems and his letters precisely because they reveal Gunn’s boldness: his eagerness to embrace not only same sex desire, but radical forms of self-transformation.

Works Cited

Als, Hilton. “The Gentleman: Thom Gunn’s Letters Reveal the Person Behind the Poems.” The New Yorker. 6 June, 2022.

Gunn, Thom. The Letters of Thom Gunn. Ed. August Kleinzahler, Michael Nott, & Clive Wilmer. Farrar, Straus & Giroux: 2022.

---. The Occasions of Poetry: Essays in Criticism and Autobiography. Univ. of Michigan Press, 1999.

Guthmann, Edward. “The Poet’s Life/ Part Two: As Friends Died of AIDS, Thom Gunn Stay healthy until his need to play hard finally killed him.” 26 April, 2005. The San Francisco Chronicle.

Lesser, Wendy. “Thom Gunn’s Sense of Movement: He Left England a Generation Ago to Seek a New Life in the Bay Area...” Los Angeles Times. 14 August, 1994.

[1] Most of these poems were written in the period before Gunn quit his teaching position and began experimenting with LSD.

[2] Gunn’s participation in a heterosexual/homosexual outdoor orgy in Sonoma County in the 1970s is documented in his poem, The Geysers (1976). The poem famously begins with rhyme and meter and ends in free verse. The transition charts Gunn’s communitarian experience of ecstasy.

[3] A legendary gay bar in San Francisco.

[4] This account of Gunn’s death on April 10th of 2004 is taken from Clive Wilmer’s Introduction to New Selected Poems (FSG, 2017).