LSD, Smiles and the Madness of Operation Julie

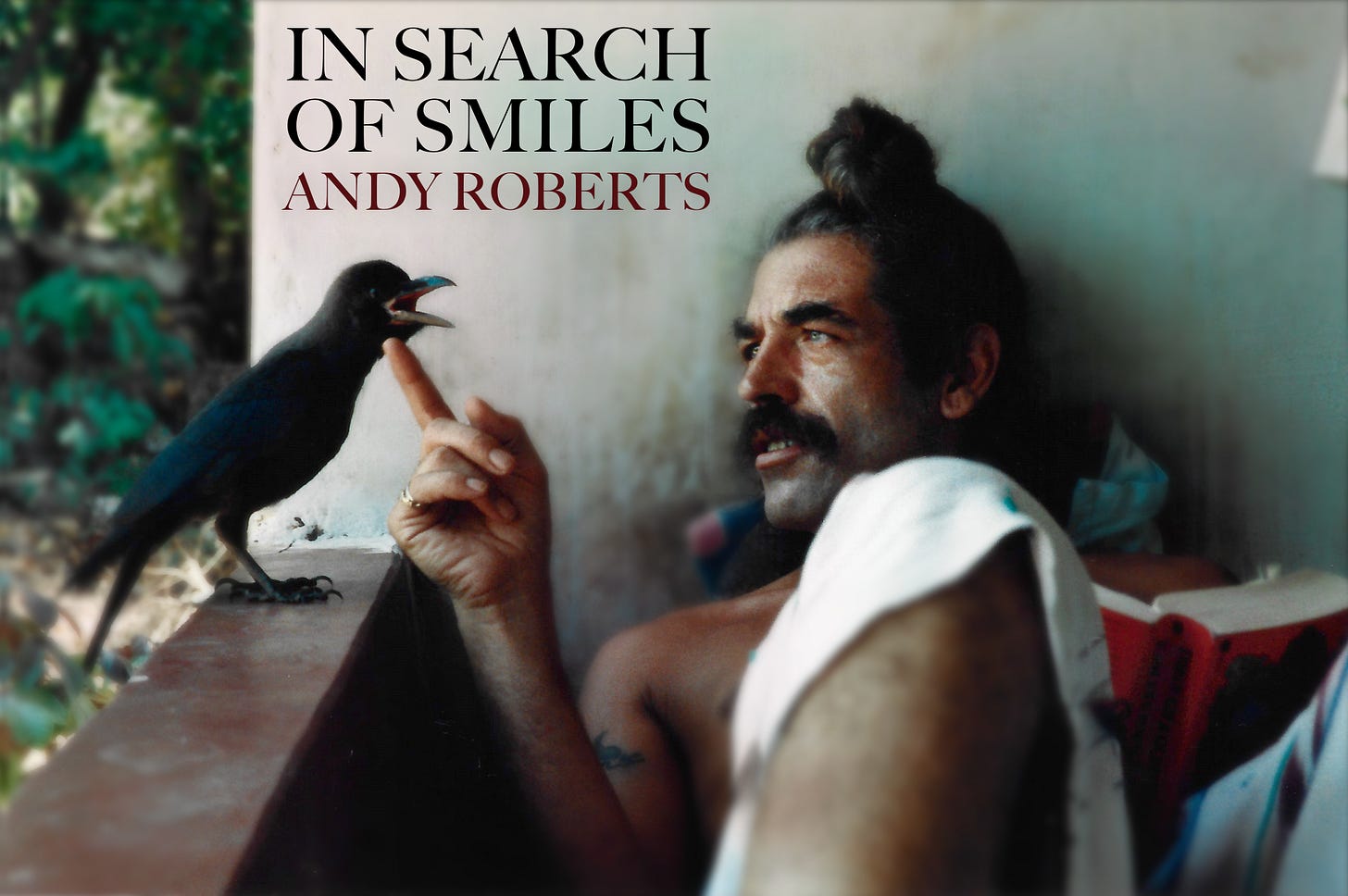

Review of 'In Search of Smiles' (2023) by Andy Roberts

In Search of Smiles is a new biography by Andy Roberts about a key figure in the Operation Julie LSD ‘Microdot Gang’ of the 1970s.

The term ‘Operation Julie’ is indelibly branded on the minds of anyone who knows anything about British counterculture in the 1970s. One of the biggest anti-drugs initiatives ever, it was tabloid heaven, with the bust itself, in March 1977, becoming the top news story of the day, its ramifications going far and deep.

In the public mind, drug busts were directed against familiar hard drugs such as heroin and cocaine, and increasingly cannabis, the smuggling and distribution of which had increased exponentially over the past decade. What made Operation Julie newsworthy was the target drug, LSD, at the time an exotic and much-feared substance; known to have inspired the Beatles and Pink Floyd, but also to have driven people crazy.

Therefore, the dynamics of Operation Julie were qualitatively different. The story wasn’t about a straightforward ‘good cops versus evil pushers in it for the money’, it was about ideology and the politics of personal experience, about LSD’s effect on society, and controlling the impressionable. LSD proponents, people who’d experienced the drug in significant doses, and who had undergone its transcendental, transformative effects, saw it as a catalyst to change the world for the better, a shortcut to ‘the meaning of life’, which, if it were to spread exponentially throughout the populace, would effect desirable societal change, one brain at a time…

That was very much the aim of the ‘Microdot Gang’, chemists Richard Kemp and Andy Munro and their supporters—a revolution, first in the head and then out in the world. Conversely, the ‘authorities’, in the form of Detective Inspector Dick Lee of the Thames Valley Drug Squad, saw it as their mission to head this off at the pass; and when seizures of LSD at street level revealed an emerging pattern of greater proliferation of high-quality product, they correctly conjectured a supermassive laboratory setup, together with a tabletting and distributing network—and this recipe for a perfect storm gave rise to Operation Julie.

Into this scenario steps Alston Hughes, aka ‘Smiles’, the subject of Andy Roberts’ excellent biography. Born in 1947, he was just the right age to hit the ’60s counterculture boom as it gathered pace, and was carried up on the crest of its tsunami. After a turbulent, troubled childhood, with an emotionally distant mother and a classic textbook abusive stepfather, he developed a rootless, peripatetic existence, naturally becoming a ‘freak’ with long hair and beard, taking to drug culture with easy aplomb. Whether in school, or in the army, or in the multitude of short-term jobs he undertook, Smiles always had the knack of getting on the wrong side of the authorities, and this shaped him for the outlaw life of his chosen profession—big-time acid and dope dealer.

For Smiles, the aforementioned ideology behind LSD was everything. He wasn’t in acid dealing for the money—though money is always welcome!—he was in it for the evangelism, the spreading of happiness. The ‘experience’, as defined by Jimi Hendrix to differentiate between those who know acid and those who don’t, was everything. Smiles himself was a heavy acid user, who invariably had positive trips on the drug—apart from one rare exception—and very much wanted to sell this to the world.

Author Andy Roberts makes this point early on, saying that Smiles had eschewed earlier offers to write his life story, on the grounds that the putative authors were not ‘experienced’ and therefore unlikely to do it justice. Andy outlines his own epoch-making initiation in 1972, which was ‘often terrifying, occasionally staggeringly beautiful, but always profound’ and had the lasting effect of ‘permanently altering the trajectory of my life’, leading to Andy becoming a keen student of drug culture and penning several books on the subject, including Acid Drops and Albion Dreaming.

I too experienced this same, ultra-strong microdot acid, doubtless made by Kemp or Munro, in 1975, and wrote about it in The Mad Artist and Man of Letters, and also in the novel The Empty Chair. In this latter work, filmmaker Steve Penhaligon discusses the psychological implications of his first trip with his therapist, and on review he concludes it was the most important single event in his creative life. ‘Everything before it was leading up to it, and everything afterwards led away.’

The original proselytising aims of the Microdot Gang were very much fulfilled in the case of two writers, Andy and myself, but it must be stressed that the power of LSD should be respected and it must be handled with great care. There is always ambivalence on a trip, and Andy’s ‘terrifying’ but also ‘beautiful’ first time was very much the case with my own. The drug’s effects are highly subjective, and to a significant extent unpredictable. It’s not for everybody, as evinced by the famous rock music ‘acid casualties’ of the late ’60s: Syd Barrett of Pink Floyd and Peter Green of Fleetwood Mac, who ruined their mental health through unwise overindulgence.

Returning to Smiles, at the time the Operation Julie task force was formed, he was living with his family in a cottage in Llanddewi Brefi, a remote Welsh village, and handling in the region of 100,000 LSD microdots a week. Two undercover cops, Stephen Bentley and Eric Wright, were embedded in the village community, styled as hippies, and given the task of befriending Smiles and discovering his activities. Smiles says he was on to their game immediately and played them accordingly; and in the end his downfall was brought about by other factors—mainly the confessions of the lower-level dealers he supplied—as no significant drug finds were made when his cottage was raided on that fateful day in the spring of 1977.

In the giant media circus that followed the bust, and throughout the trials of the Microdot Gang, no quarter was given in portraying them as arch villains. The presiding judge, Sir Hugh Eames Park, refused to make any concessions for the ideological motives of the defendants, considering financial profit to be the only one. He also refused to differentiate between LSD, a non-addictive psychedelic, and other Class A drugs such as heroin, and the sentences handed out were correspondingly harsh, if not harsher. As chemist-in-chief, Richard Kemp received the longest sentence of thirteen years, and Smiles himself, as a mid-level operative, got eight years.

Including time on remand, Smiles served nearly five years, and much of his incarceration was spent keeping the hippy dream alive by smuggling cannabis and LSD into prison through many ingenious methods. Released into the dour Thatcherite British landscape of 1982, he picked up the threads of the old life, staying stoned with friends such as fellow Microdot Gang member Leaf Fielding, and travelling around India in search of the ultimate hashish; high in the mountains, in more than one sense. Now seventy-five, he lives happily in semi-retirement, co-running a cannabis seed mail-order business (which is legal) and enjoying his status as a counterculture legend.

Throughout In Search of Smiles, Andy Roberts demonstrates great skill as a biographer, processing a mass of intricate detail about a life, which allows us to really know the subject, yet keeping up the narrative pace in an extended rush of vibrant energy—almost like a drug trip in itself—to produce an edgy, page-turning drugs thriller, comparable to Howard Marks’ Mr Nice, and evoking the same nostalgic Technicolor vistas of the Golden Years of Hippy Culture, which seem so naïve now from the perspective of the present.

The biography also adds many useful new perspectives to the burgeoning literature about Operation Julie. As early as 1978, Inspector Dick Lee had a book out, written with journalist Colin Pratt, giving the cops’ side of the story. Two of the undercover cops involved, Martin Pritchard and Stephen Bentley, separately wrote their accounts of the proceedings, and Leaf Fielding gave us his autobiography, crafted from the ideological, hippy perspective, to even up the score a little. Also, journalist Lyn Ebenezer—the only ‘civilian’ to write a book about the operation, as Andy Roberts said wryly at the time—gives a more balanced overview of the Julie phenomenon. More recently, James Wyllie, mainly known for books about the Nazis, has given yet another broad overview.

As for the acid chemists involved, both Richard Kemp and Andy Munro have remained tight-lipped about their roles in the Microdot Gang—though Andy Roberts says Munro was cooperative in regard to the biography. Kemp’s statement about his motivations for manufacturing acid, ‘Microdoctine’, written for his defence at his trial, but not used on legal advice, did see the light of day recently, as the climax of Operation Julie: A Rock Musical, which was staged in theatres in Wales in the summer of 2022 to great acclaim, with both Smiles and Andy Roberts acting as advisors during development. [Rumour has it that this highly acclaimed enterprise will be returning the stage in the future! Ed.]

Kemp’s outpourings, considered damaging to his legal defence, are, of course, a reiteration of the ideological stance of the Microdot Gang—their hopes of making humanity and the world a better place through mind expansion. As Smiles himself says on that front: ‘The only true revolutionary thing we can do is change ourselves and there’s no better agent than LSD to have helping in furtherance of such change!’

Today we hardly live in a state even approaching a utopian society, but that was always an impossibly high bar to begin with, for a chemical or any other single entity. But nevertheless, LSD did change the world, through a subtle ‘revolution in the head’, its effects deep and far reaching, permeating in ways the straight ‘inexperienced’ population can hardly begin to imagine.

LSD has transformed popular music, obviously, from Sgt. Pepper and acid rock, to prog rock, jazz-rock fusion, acid house, acid jazz, funkadelia; and it laid the foundations for techno, trance, trip hop and similar genres. And those who are sensitive to the vibes can detect its huge influence on art, literature, cinema, TV, pop videos and VJ presentations, graphic design, advertising, philosophy, computer technology (Steve Jobs was famously ‘experienced’), and the whole postmodern revolution in ideas that has given us 21st century life.

The renowned—and ‘experienced’—post-structuralist philosopher Michel Foucault poses the question of ‘whether drugs have sufficiently changed the general conditions of space and time perception so that non-users can succeed in passing through the holes in the world and following the lines of flight at the very place where means other than drugs become necessary.’

It’s beyond doubt that LSD and similar substances, aided by its proponents, such as the Microdot Gang, have achieved that aim. And in this book Andy Roberts pays affectionate tribute to the intense lives of those who did the ground work.

In Search of Smiles is available from psychedelicpress.co.uk, Amazon and other retailers.