During the Victorian period microscope technology developed in leaps and bounds. It afforded many more people the chance to examine the minutiae of the natural world in ever greater clarity, fueling their imaginations. In keeping with the era’s fancy for fairy literature and artwork, it was not unusual for naturalists to describe what they saw in these terms. As the writer and science educator Arabella Buckley wrote, ‘the slime from a rock-pool teems with fairy forms darting about’. These devices were quite literally revelatory.

This discourse neatly illuminates how technology has the power to simultaneously enchant and disenchant. In one sense, microscopy reveals the previously unseen and unexplored. The hitherto mysterious realm of the very small has a light shined upon it as the mechanisms of the natural world are revealed in ever more spectacular detail. In another, however, this new domain raises many more questions as people realise that this world, ordinarily hidden to our senses, teems with life and strange, new forms.

Capturing an image of fairy world is no mean feat, but in respect of microscopy this has become an ever more detailed and curiously stunning endeavour as we have developed the tools to do so. It is a borderland of science and art that fascinates as much as it teaches. In Microcosms: Sacred Plants of the Americas, Jill Pflugheber and Steven F White have given us a glimpse into the inner botanical workings of some of world’s most enigmatic plants.

Microcosms originally began life as an exhibition at St Lawrence University’s Brush Art Gallery in March 2020, titled A Homage to Sacred Plants of the Americas. However, it was forced to close after only two weeks due to the pandemic. The book greatly expands on the exhibition with images and context, and is also an extension of two other exhibitions, both curated by Professor Luis Eduardo Luna, called Visions that the Plants Gave Us and Inner Visions: Sacred Plants, Art, and Spirituality.

Plants that are sacred to various indigenous peoples throughout the Americas are the subject of this book then. These include those famous for their psychedelic properties such as Banisteriopsos spp. (the vine used is ayahuasca), Lophophora williamsi (peyote), and Salvia divinorum, along with notably famous plants like Erythroxylum novogranatense (coca), Cannabis sativa, Nicotiana rustica (tobacco), and many, many others too. Indeed, almost fifty plants are discussed and shown in beautiful, microscopic detail.

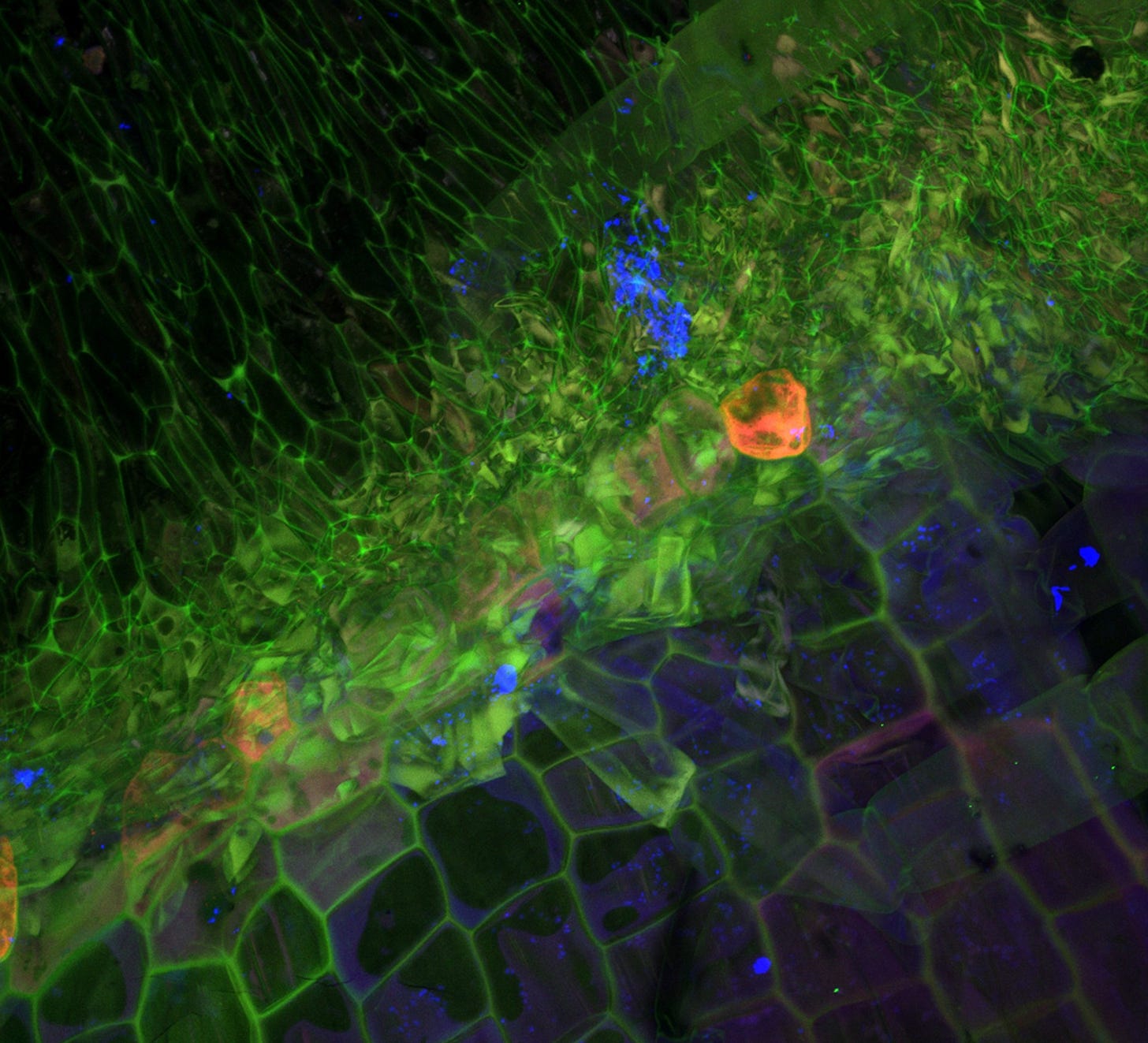

The stunning images are created using confocal microscopy, also called confocal laser scanning microscopy, which is a ‘specialised optical imaging technique that provides contact-free, non-destructive measurements of three-dimensional objects.’ This technique creates ‘optical sections through layers of biological samples.’ Basically, naturally occurring fluorescent chemical compounds release photons which are gathered over a period of time, constructing the image.

Microcosms also includes a thoughtful discussion of its antecedent practitioners, from Robert Hooke (1635-1703) and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) through to the modern day. This is useful for the reader in order to understand how the threshold of art and science has shifted over hundreds of years, as changes in technology, styles and ideas jostle with one another. It lays the ground work for what Alexis Rockman has described as ‘a hybrid language that is natural history psychedelia’—a phrase aptly describing this book too.

The inner botanical worlds revealed by ‘Microscopic Phytoformalism’ are beautiful, ethereal and, in some respects, liminal worlds. The authors quote artist and professor György Kepes (1906-2001) in this regard, that ‘a pattern in nature is a temporary boundary that both separates and connects the past and the future of the processes that trace it.’ The captured images are thus inhabited by a kind of Whiteheadian process that persists in consequence of what we see, threading a kind of living memory through the captured aesthetic.

Wonderfully presented in a large format, Microcosms gives apt justice to the incredible imagery it displays. Together they teem with an spectral array of blues, greens, and occasional warmer colours, in myriad forms—each with a different sense of movement. The sacred plants themselves have a diverse range of effects and uses in the Americas, and their inner worlds are equally as fantastically different. Coupled with discussion and ordinary botanical photography, one gains a real sense of each plant in the fullness of its being.

As an example of the space in which science and art meet, Microcosms is an excellent and thoughtful contribution. As with any decent ‘coffee table book’ it will be worth revisiting many times over. It is shot through with inspiration, both artistic and otherwise. As a kind of architecture of sacred plants, the imagery teaches us that other worlds, be they fairy-like, microscopic, or DMT-induced, often have a mysterious and enchanting logic all of their own.

San Pedro Cactus

I love this, thank you!