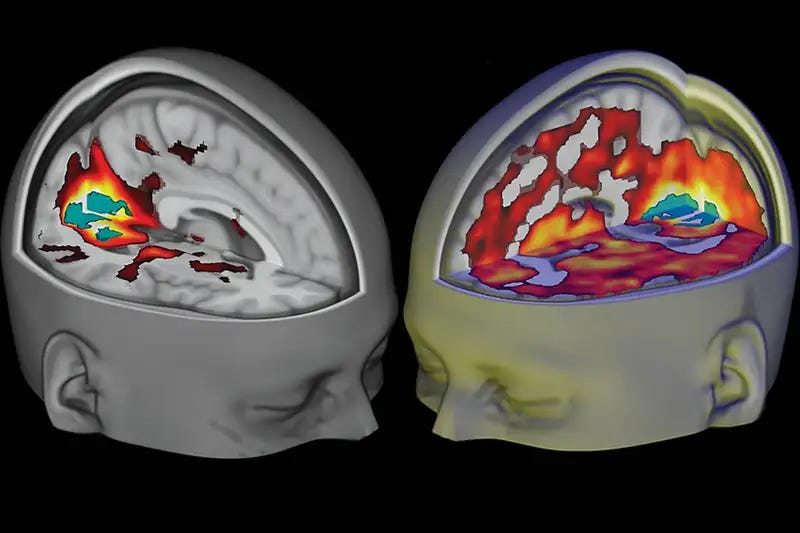

The resurgence in psychedelic neuroscience has been gathering pace for over a decade and has, in many respects, been about implementing a twenty-first century upgrade. The Imperial College team, for example, uses the very latest neuroimaging equipment to study the effects of different drugs in the brain.

Fifty plus years ago, the technological landscape was quite different. The Positron emission tomography (PET) and Magnetoencephalography (MEG) were still in their infancy, while Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was decades away from discovery. It is now possible to discern a far more complex picture of psychedelic action in the brain.

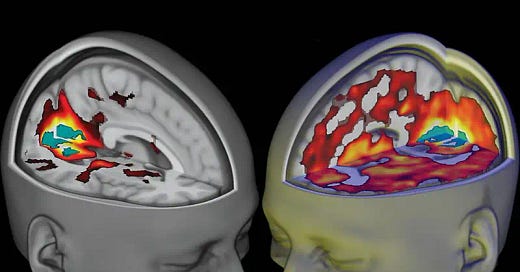

By 2016, the Imperial team had also revisited the most iconic of psychedelic substances, LSD, when they undertook a multimodal neuroimaging study looking at neural correlates in subjects. In it, they re-identified a suppression of alpha waves, and a change in the integrity of the Default Mode Network (i.e…