Meta-Cultural Drug Aesthetics

Review of Drug Culture: A History of Psychedelic Art, Part 1 by Paul Farmer

The way in which humans aesthetically express their relationship with drugs is like looking out upon shifting sands; it is constantly reforming with the winds, expressing sometimes stark, sometimes subtle new vistas, depending on your viewpoint. Time and place intersect, creating a cultural milieu, through which individual and social drug experiences refract. The relationship between the individual experience of a plant, fungi or substance and its aesthetic/artistic expression is rarely fruitfully understood as a simple binary; they are to some extent mutual symptoms of a milieu.

What then is psychedelic art? Answers to this question might range from objects that have been created by someone under the influence of a particular class of drug; an aesthetic style associated with a 1960s subculture; art that expresses the otherworldliness associated with the psychedelic experience and which, psychologically speaking, is accessible to humans across times and cultures; or, indeed, anything that manifests from the mind. In short, it is a question that first requires you to define your context, your evidential milieu, before it can be answered.

‘Psychedelic drugs with their roots deep in human culture,’ writes Paul Farmer, ‘have been eaten, drunk, snorted or smoked through almost the entire world and for the whole of human history.’ In Drug Culture: A History of Psychedelic Art, Part 1, Farmer has selected a wide-range of imagery from the corpus of human artwork. Some of it is clearly drug-inspired, either positively or negatively, others are windows into drug-using cultures or symbolic representations. The mind-altering agents in question are neither pharmacologically-strict, nor necessarily visible for the viewer.

Drug Culture (Part 1) casts a very wide net in approaching the question of drug aesthetics, taking in cultures from around the world up to the post World War Two era of psychedelia. In regard to the ancient and prehistoric, Farmer looks at a number of interesting artefacts. The tattoos of Scythians, a people who Herodotus noted used hemp smoke in vapour baths, and which recent archeological excavations have confirmed, are a less obvious example. While Tantric art and the Eleusinian Mysteries are far more well-known ones.

Without doubt these cultures used psychoactive plants yet the manner in which their art reflects this relationship is more interpretive, more esoteric in their potential meanings. Shifting to late medieval witchcraft, with which certain solanaceous plants such as belladonna are connected, woodcuts emerge that apparently depict the experience of those who use ‘flying ointments’. Given that this narrative is so readily embedded in contemporary critical approaches, the art is a kind of construction of fearful imaginations, which neatly brings to mind twentieth century anti-drug propaganda.

The manner in which the interpretation of drug aesthetics is construed brings to light interesting questions. ‘Was Hieronymus Bosch a psychedelic artist?’ Farmer asks. The link between Bosch and ergotism, or St Anthony’s Fire as it was then called, has been made before, although Farmer also looks at the possibility that a mushroom may have been involved. He does concede that systemic magic mushroom use does not appear in Europe until more recent times, and that ultimately, his work is best analyzed through ‘its actual context rather than a fanciful one’.

Other cultural geographies that this book is concerned with include Persian art, the Mughal dynasty, and Siberian shamanism. The images of paintings and artefacts provides a clear differentiation between the stylistic approaches of such disparate groups of people. Through this, it is possible to see how any association with drugs is completely subsumed into unique ritual, social and aesthetic preferences. What emerges is that the fact of drug use is more fruitfully understood as a window into the being of such cultures, rather than other way around; the cosmologies of altered states.

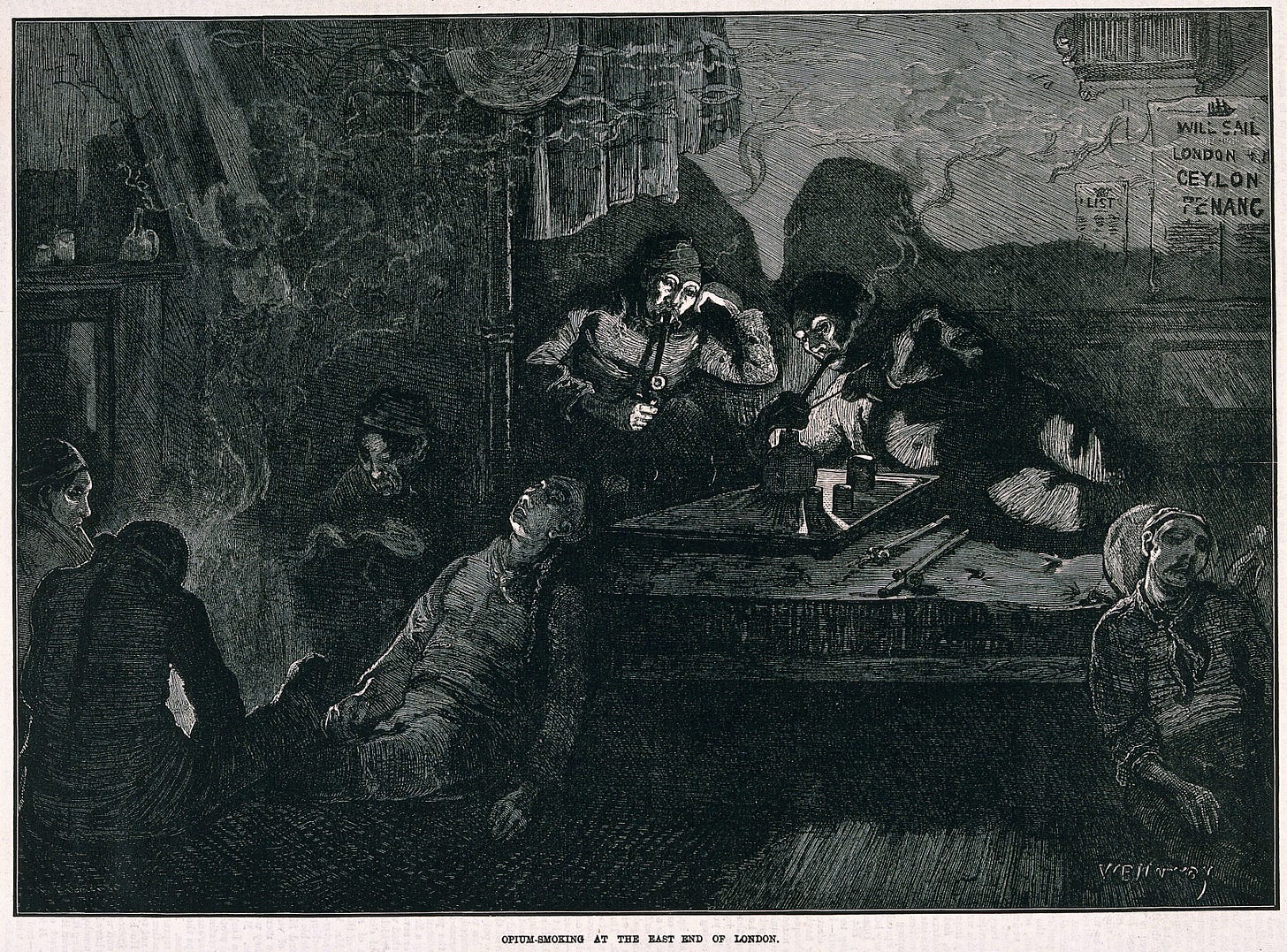

The final third of Drug Culture shifts into a more Western, post-Enlightenment focus. It begins with Orientalism and the Western engagement with the East, particularly through the prism of opium and hashish. Indeed, through these substances, Farmer drives his narrative into the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Images of hookah smokers and opium pipes users in exotic clothing precede a shift into John Tenniel’s hookah smoking caterpillar, designed for Alice in Wonderland, and the arch-mage and poly-drug user Aleister Crowley in robes.

Concerning Crowley, Farmer writes, ‘As a practitioner of ceremonial magic, his legacy is negligible. Very few people dress-up and perform elaborate rituals today, but his association of sex, drugs and magic survives him’. I would suggest that no-one can understand ritual, ceremonial magic from the twentieth century to the modern day without some recourse to Crowley – it is far more widespread now than then. His influence is pervasive. Nevertheless, ultimately he bequeathed to, what Adam Curtis has called, the ‘century of the self’ with its core radical individualism; the remaking of identity.

Farmer ends Part 1 at this point, noting that Hofmann was simultaneously discovering LSD. It is, to my mind, a fitting place to do so. The aesthetics of psychedelia, so much concerned with individual and social transformation, seem as much a legacy of Crowley as it is Freud or Jung. Drug Culture does not, nor does it try, to definitively answer the question, what is psychedelic art? What it does, and admirably so, is explore the limits and ideas through which one might approach the question as a meta-cultural aesthetic founded upon the ubiquity of psychoactive substances.

Learned a new word, "solanaceous" from this essay. There is a typo in the second to last paragraph, if you care. "His influence HIS pervasive". 🍄

How does one get access to this book?