The mythopoetic features of tripping, as an aesthetic, pervade our experience of a drug both prior to, and long after, its effects are felt. It is cultural and exists beyond ourselves for we are simply its manifestation—a mushroom to its mycelial network. Trippers, with very rare exceptions, are explosions within the mythopoetic narrative; they are of the story, not its progenitors, and in this respect, the stories (myth) and the artefacts (poetry) of psychedelia exist in a loopy aesthetic continuum mediated in part through experience. LSD blotter is one filament in this process.

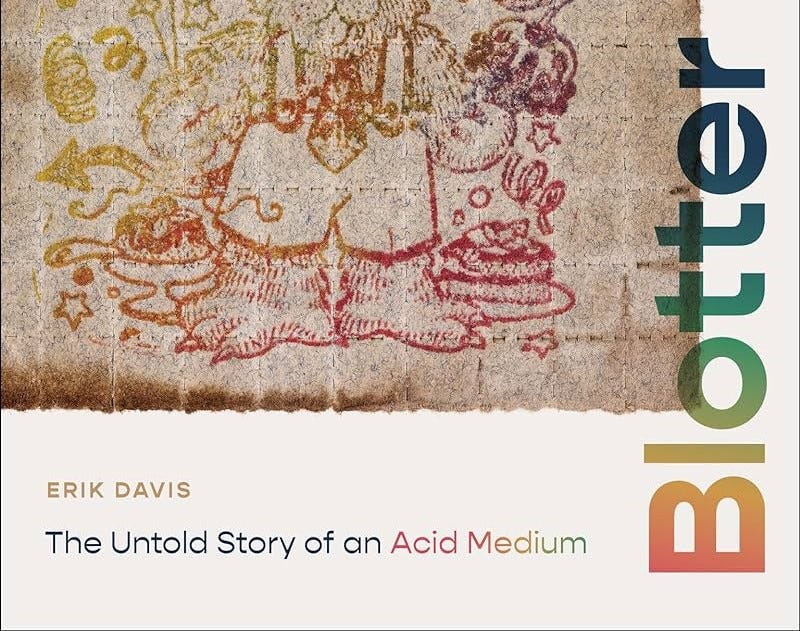

‘Bodies of drugs matter’ writes Erik Davis in Blotter: The Untold Story of an Acid Medium (2024). Take, for example, the legendary LSD chemist Augustus Owsley Stanley III who, with co-conspirators Melissa Cargill and Tim Scully, produced a large batch of pure acid, then distributed it in five separately coloured tablets. Although the same chemical substance underpinned them all, each acquired their own character on the street—mellow, speedy, spiritual. In short, a varied aesthetic wrapped up with the medium’s form had far reaching disparate and mythopoetic effects.

‘When you print images onto a paper carrier medium,’ Davis notes, ‘you are adding another layer of mediation to an already loopy transmission.’ Blotter is a medium for delivering LSD, it is also art, historical artefact, a media or ‘meta-medium’. Acid blotter swims between the currents of psychedelic aesthetics. As a postwar phenomenon, acid blotter is also wrapped up with an era of increased consumer advertising and the explosion of electronic and digital media. Yet, it exists in a subterranean strand of the era’s culture, a place that traverses danger and outlaw lifestyles.

From its earliest manifestations in late 1950s Britain as a simple blank medium to distribute liquid LSD, blotter was perfected as a method of distribution and artistry across the pond, where it was subjected to the ‘mechanical reproduction required to level up to a properly commercial scale.’ Eric Ghost and a colleague developed a machine with a system of 100 pins in a grid, simultaneously dipped in LSD, then impressed onto absorbent paper. New varieties of systems were developed by Ghost and others and by 1970, the term ‘blotter acid’ was well established in LSD circles.

The production of images in the early years often involved handstamps by dealers who made their distinguishing mark on the product, or else silk screens and lithograph methods were used slightly higher up the pyramid chain of LSD distribution. Really taking off as a method in the 1970s, a myriad of images were employed from the deeply esoteric and occult through to cartoon characters and superheroes. In the late 1990s, blotter imagery also developed into a more distinct artform with ‘vanity blotter’—essentially acid blotter without the acid.

As Davis acknowledges, trying to write a history of an underground culture, which by its very nature is secretive due to the illegal practices with which it is associated, is a necessarily difficult task—much must remain ‘untold’ even in the telling. Aside from a cadre of named and unnamed informants, there are two very important sources that Davis uses to begin to weave together his Blotter story, which is part history and part art criticism.

The first, rather remarkably, is the internal Drugs Enforcement Agency (DEA) publication Microgram. From the late 1960s, Microgram collated and reported all the information from crime labs across the United States and occasionally beyond, including, in 1987, the LSD Blotter Index. A complete run has been made available by the diligent and always brilliant work of the team at Erowid. Ironically therefore, ‘the agencies tasked with destroying the scourge of LSD were in essence the first collectors of the genre.’

The second is collector, archivist and artist Mark McCloud, founder of the Institute of Illegal Images (III) in San Francisco, and who has done more than any other individual to transform the acid medium into an artform. Starting his collection around the turn of the 1980s, in 1987, through the San Francisco Art Institute, McCloud put on ‘The Holy Transfers of the Rebel Replevin’, a dedicated art show. Small individual or 4-way tabs were shown and visitors were provided with magnifying glasses. More shows soon followed.

During the 1990s and at the turn of the millennium, the DEA and public prosecutors ramped up their efforts to shut down the illegal manufacturing and distribution of LSD. McCloud, collector and blotter producer, was a very public face of these efforts. In 2000, the DEA packed up the contents of the III and McCloud was up in court in Kansas City the following year. The case is well told by Davis and rested on an important question: were images on blotter art? Some were certainly sold as such. The jury deliberated for over 10 hours, and he was thankfully acquitted.

Blotter art as a commercial venture is one aspect, notable in modern ‘vanity blotter’, however it is also something more. Adding images to blotter may sometimes have added some market value to LSD but, as Davis points out, it is not clear whether this justified the added labour involved. People in the main were buying acid not images. ‘In other words, images on blotter are essentially superfluous. Their worth derives from a sort of phantasmagoric excess, an iridescent surplus of signs and patterns that communicate values—beauty, humor, swagger, magic, love—that outrun market logic.’

It is these values, the mythopoetic, that makes Blotter so fascinating. It is a beautifully written book with hard won research that manages to describe an incredibly obscured subject with thoughtful insight, humour, and Davis’s usual flair for storytelling. It includes a plethora of wonderful images with not only the author’s commentary, but a host of other insightful contributors too. I can’t recommend it enough.